Before we were Proud.

This project documents the personal histories of members of the LGBTQ community who were around before the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967.

Members of the LGBTQ community still endure prejudice, but if you were a young adult before 1967, there was not only the risk of physical and verbal abuse, but there was also the risk of arrest and imprisonment.

Britain is slowly becoming a more open-minded country. Every year, the Pride March has become a celebration of LGBTQ culture, but many people don’t realise that it started as a protest, and those brave enough to attend back in the 1960s took considerable risks.

This ongoing project aims to tell the stories of these courageous people.

Gerald Moon

Gerald Moon was sweeping the path of his Balham house when I stopped to take these shots. The very first thing he told me was, "I have given my life to the theatre."

He's done it all—acting, directing, writing, and even washing the glasses in the interval. "It's a remarkable life, and you quickly develop a thick rhinoceros's skin for rejection. When you are young, it hurts, but it gets easier when you are older."

Throughout his career, Gerald has appeared on many stages, TV shows and films. The 'Zenith' was when he performed as King Herod in the West End production of Jesus Christ Superstar in the 1970s.

He also got lots of advertising work because he has a 'cheeky face.’ One of his favourites was being flown to Rio de Janeiro to appear in a commercial for Kodak film cameras set on Copacabana Beach. He was also, for a while, the face of the 'Double Diamond Works Wonders' beer campaign.

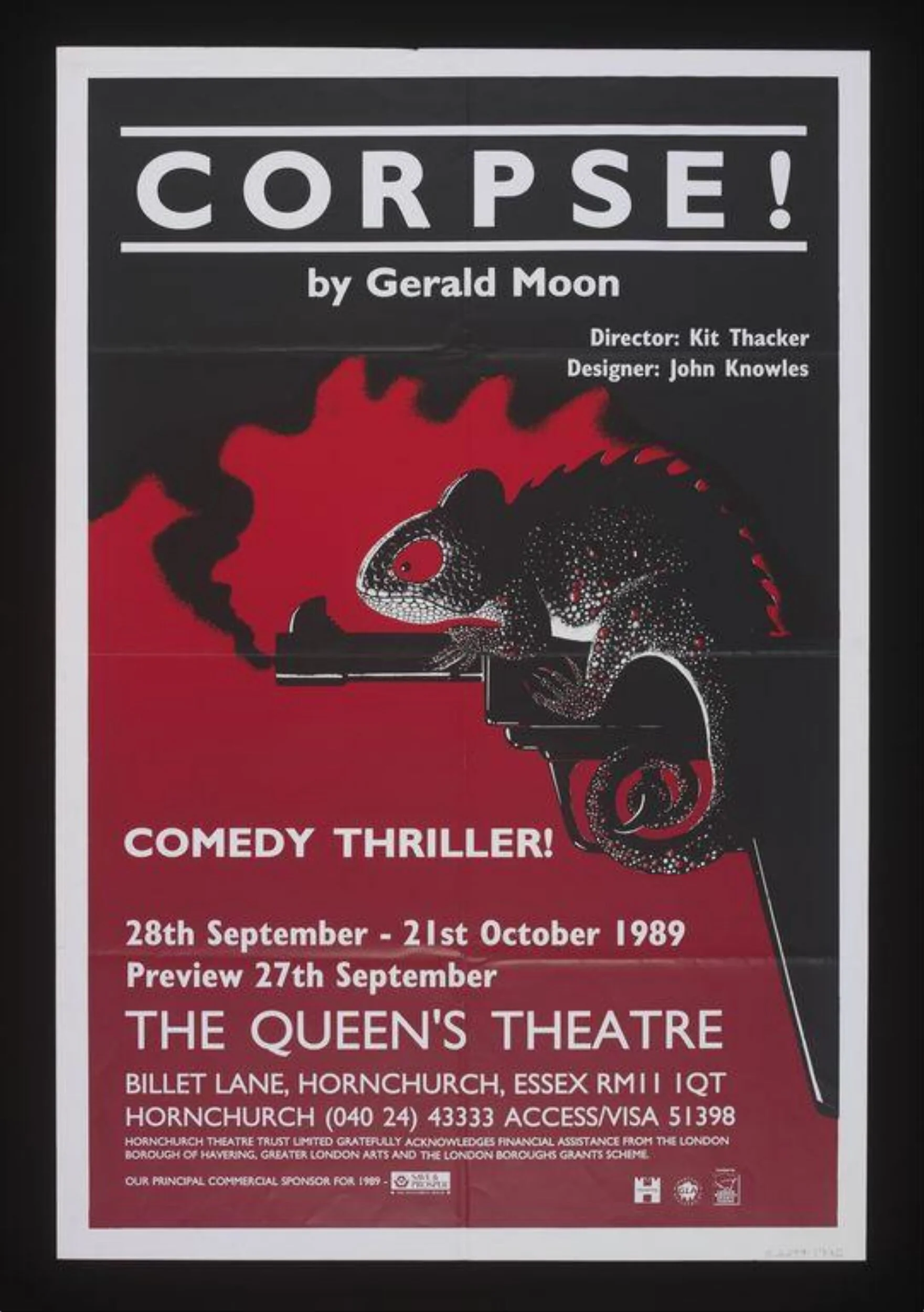

In 1969, Gerald wrote a comedy thriller, 'Corpse,' about twin brothers, one of which plots to murder the other in unusual circumstances. He tried to sell the script all over London but was repeatedly rejected.

So he put the script in a suitcase and took it to New York. The very first person he showed it to was a producer whose dream was to put a play on Broadway. He got Corpse to appear in a few regional theatres before the producer's dream came true, and the play, starring the actor Keith Baxter, ran on Broadway.

The play was a huge success, with two runs in London's West End. It has since appeared in 29 countries.

Corpse 'opened up the world' for Gerald because he travelled to far-flung places to oversee and sometimes act in the productions. The residuals also allowed him to write the 'biggest cheque of my life' when he bought the house, which, after 46 years, he still lives in today.

Gearald’s play ran on Broadway and all over the world.

Around this time, Gerald was at a party in Bayswater, "full of theatrical types, all trying to outdo each other as usual." It was then that he was introduced to David.

Gerald immediately took to David as he was charming, personable and smartly dressed. The couple clicked and remained together for 32 years until 1996 when David died of spine cancer.

David was a Lay Buddhist at the temple in Wimbledon, so when he passed, Gerald arranged a full Buddhist ceremony with 300 guests and all the monks in their robes. Gerald told me it was a terrific send-off, but he still misses David.

He now lives alone but remains cheerful; "Life has treated me exceedingly well, and I count my blessings daily."

Gerald told me that it was terrible being gay in those early days when homosexuality was illegal. He said, "I was born a criminal and had to lead a double life".

At his church, nobody knew he was gay, and he hated having to hide his true self. However, he also confided that, at times, it was rather exciting because "I had a secret, and young people love having secrets."

Things did improve; the coming of the swinging sixties meant that being gay, at least in London anyway, started to become slightly more acceptable and open. Gerald loved the King's Road and visiting clubs such as The Boltons, The Casserole, and the Coleherne. To David, this was glorious because he suddenly realised he wasn't the only one in the world.

As a gay man born in the 1940s, Gerald told me that he never imagined that he would live to see the following three major events in his life.

The Theatres Act of 1968 allowed actors to say whatever they liked on stage.

The 1967 Sexual Offences Act which decriminalised private homosexual acts between men aged over 21

The 2013 (sex same couples) act allowed gay couples to get married.

In Gerald's words, "The world has changed so much in my lifetime, and it's been fantastic."

Gerald's rather unusual garden made me stop to take a picture. He had such an interesting life that I completely forgot to ask him about it.

RIP Gerald Moon, 1943-2023

Jade

Jade was born in 1956 in Toronto, Canada. Her mother had dual nationality and brought Jade back, firstly when she was four, to meet relatives and also to have treatment for astigmatism. Although Jade and her mother then returned to Toronto for a period, they eventually came back to England permanently at 15, taking up residence in her mother’s hometown of Ulverston in Cumbria. Also known as the home of Stan Laurel (of Laurel and Hardy fame) and not far from the birthplace of the founding of the Quaker religion, Swarthmoor Hall.

At school, Jade thought the other girls’ obsession with boys was highly amusing. Her two best friends were boys, but there was no romance, just cider-drinking and mucking about while perched in a tree overlooking the churchyard.

Jade was becoming aware of her attraction to other girls, but in the small community where she lived, the concept of being gay was such an abstract notion that she never really thought about it.

After secondary school, Jade wanted to pursue A levels and attend university, but her mother insisted that she get a job instead. She joined the secretarial pool at South Lakeland District Council in Kendal. After a time, she began dating a young man from nearby Barrow-in-Furness, who was at University in Birmingham and home for the holidays. While her feelings for him were genuine, she felt something was missing.

It was the 1970s, with flower power and hippies in places like London, but in the part of the world where Jade lived, it was more like the 1930s. Jade remembered going to a working men’s club with her boyfriend. She went to the bar to order drinks, but her boyfriend, shame-faced, told her the maitre d’ had sent him over to ask her to sit down, as women weren’t allowed at the bar. Jade promptly ordered a large cigar with a pint (unheard of for women to order pints, let alone cigars) and spent the whole evening standing at the bar, puffing her cigar and occasionally grinning at the none-too-happy maitre d.

At 19, while shopping with her mum in Manchester, Jade stumbled upon a women’s march protesting changes to abortion rights. The sight of outspoken, motivated women awakened something in her. She joined the march, collected leaflets and immersed herself in feminist literature.

After working at the council for three years, Jade was still determined to attend University, completed “A” levels at night school, applied for a grant and studied English in Birmingham. She and her boyfriend lived in Tamworth, a conservative satellite town to Birmingham, where women in pubs without men were frowned on, and she was once questioned by an apologetic female worker (the landlord sent her over) as to whether she was a prostitute!

Fortunately, Jade discovered the local women’s group. There were about ten women in total, and they supported domestic abuse victims, organised political campaigns and advocated for a women’s refuge.

Jade’s activism continued with the Greenham Common protests against nuclear weapons. After the women’s group hired a coach to visit the camp with local women, Jade just had to go back. Initially, she took the train from Tamworth to Newbury in Berkshire, delivering funds raised by the group for the camp. However, after getting to know the women at Greenham better, she was inspired to quit her job, leave her boyfriend, and join the group full-time.

Greenham became her sanctuary – a place where she could embrace her identity and stand up for what she believed in. It was here that she met her first girlfriend and found a profound sense of belonging.

During her time at Greenham, Jade, as a part of networking for the camp, went with two friends to Vancouver to talk to other women there about the peace camp. While there, she met members of the indigenous community protesting uranium mining on their lands. Also, while in Canada, she stayed on a women’s herb farm on Vancouver Island, which started a lifelong interest in herbal medicine.

After returning to England, she eventually left the camp and moved to London, where she secured housing in a tower block in Deptford. She also began studying herbal medicine, qualified as a practitioner, and went on to become a self-employed medical herbalist, publishing a book on the subject.

She supported herself with various jobs, including being a reader for the blind, and eventually met her partner at a Labour Party event; the two quickly fell in love. They decided to have a child through assisted conception with donor sperm from a close family friend. Some of the nurses at the hospital refused to treat a lesbian couple, but the woman consultant was more enlightened and agreed to oversee the whole process personally.

The couple had a baby girl. Not long after, they moved to Furzedown, SW London. Initially, they had concerns about how they would be received in the new community as a lesbian family, so, typically, Jade decided to confront the problem head-on.

She went to the local hairdresser. While having her hair styled, Jade told the hairdresser that she’d just moved into the area with her family. When the hairdresser asked about her husband, Jade replied, “I’m a lesbian, and my partner and I have a daughter.”

Jade believes that being so open so quickly meant that the community immediately accepted her. She also knew that telling the local hairdresser was the best way to spread the word. Jade still goes to that hairdresser today and has become lifelong friends with many of her neighbours.

On a subsequent trip to Canada, Jade had bought her daughter a journal to record the journey. She noticed that her daughter had written that she would love to meet her biological father. With everyone’s consent, Jade organised this, and the meeting took place with regular visits between them. Jade remembers that it was a lovely moment for them all and quite poignant because a few years later, he passed away.

At about the same time, a teacher friend encouraged Jade to pursue a career in education. The only problem was that, having attended a small provincial school, Jade didn’t have a GCSE in Maths. Jade did an evening course, got the GCSE, and started working as a teacher at a local school. She did her teacher training on the job and worked there for over twenty years as an English teacher.

Jade and her partner are no longer a couple, but they remain friends. Jade continues to live in Tooting. Their daughter is now an adult and lives in New York. When she comes to Britain, the three of them spend time together.

Jade has been retired for three years. Having been a South London teacher for twenty years, she’s understandably taking it easy for a while.

Jade’s life has been defined by activism, resilience, and a steadfast commitment to being true to herself. Although her journey may have been unconventional, she has successfully raised a child, owns her own flat, and has a large network of friends - accomplishments that anyone would be proud of.

James Carrington

Jamie got his top in Primark.

James Carrington is 75 - All his friends call him Jamie. He told me that Carrington isn't his real name anyway. He invented it to erase his family when he came from Nottingham to London when he was 18.

"They are all dead now, and it's glorious. The last of them died when I was 53, and I thought, finally, I am free to be who I want to be."

He's lived in Balham for years and loves how multicultural the area is. When I took this shot, he was sitting on a bench 'watching the world go by'.

He got his top in Primark, and he loves it. He said that a young friend bought one at the same time but won't wear it out on the street. "He doesn't have my confidence," Jamie told me. "When you hit your 70s, the edit button falls off, and you stop caring what people think."

Stephen Temple

Stephen first became aware that he was gay when he was a teenager at Rugby School in the mid-sixties. Some of his schoolmates were uninhibited, but Stephen was far too innocent and terrified to get involved.

After finishing school, he worked as a language teacher in Kenya before returning to Oxford to study classics.

He had many friends, some of whom he was attracted to, but Stephen never did anything. He was too ashamed and repressed back then.

Nowadays, this is known as 'Internalised Homophobia’, but back then, this term didn't exist. Being gay was something that was rarely talked about. There were hardly any openly gay people on TV or in the media, and no role models. Despite having lots of friends, Stephen felt so very alone.

He remembers being at a disco and seeing a boy dancing. He looked so free, relaxed, and confident - it was captivating. Stephen was desperate to talk to him but felt too inhibited and couldn't bring himself to. He ended up chatting all night with a girl and went home feeling disappointed.

Things improved when he got a job in London. He worked in computing writing software. In those days, there were no computer courses, and employers felt that a classicist had the right mindset for the job.

In 1981, Stephen went to a gay disco in Stepney run by nuns, where he met Richard.

Richard was a few years older than Stephen, and at first, Stephen didn't find him that physically attractive.

But the next day, they both found themselves sneaking looks at each other at the local Quaker meeting house in Hampstead.

Stephen is a Christian and comes from a long line of clergy. His father was a bishop, and his great-grandfather was the Archbishop of Canterbury. Stephen considered entering the clergy himself but didn't because of his sexuality.

After the Sunday service, a friend invited Richard and Stephen to lunch. The friend pushed them into a bedroom to get to know each other properly.

They spent two hours in the bedroom, and all they did was talk, but during this time, they both realised that there was something special between them.

At first, their relationship was long-distance as they worked in different parts of the country.

Eventually, they moved to London and bought a flat together in Clapham Old Town.

Now that Stephen had a partner, he felt that he had to tell his parents that he was gay. His dad, being a bishop, added to the complexity of the situation.

He spent a whole weekend worrying about it and finally wrote each of them a letter. It was a nerve-wracking experience waiting to see what happened after he posted those letters.

Both parents replied with loving and accepting notes. Even now, decades later, Stephen gets emotional thinking about the lovely words that his mother wrote to him.

A few years later, Stephen's mother had her own coming out. She was at a church meeting where someone started making derogatory comments about homosexuality. Stephen's mum stood up and said that she had a gay son who she was incredibly proud of and that she had met his friends and thought that they were all so lovely.

After the meeting, a woman came up to her and said that she was so grateful to hear Stephen's mum's outburst as she, too, had a gay son and was in torment because her husband refused to have anything to do with him. The two women became friends for many years after that.

In 2007, Stephen and Richard made their relationship official at a civil partnership ceremony at Holy Trinity Church on Clapham Common.

Richard wasn't as religious as Stephen, but they often prayed together.

They remained a couple for 34 years until Richard was diagnosed with a brain tumour. His health gradually declined, and he ended up in a wheelchair. Stephen remembers one beautiful summer day; they had friends over, and Richard suddenly started talking gibberish. He was having a seizure caused by a bleed on the brain. He passed away in 2015.

Being a gay man born in the 1950s has not been easy; Name-calling and verbal abuse were a part of life back then, and Stephen was mugged twice on Clapham Common. When he was younger, he would always cross the street if a group of young men were walking towards him. Lately, he's started to do this again.

The Aids pandemic was a terrible thing to live through. Stephen volunteered as a buddy for the Terrence Higgins Trust charity. He witnessed so many young men succumb to the virus utterly alone because they were too ashamed to tell their parents that they were gay or because their parents had disowned them. It was heartbreaking,

Over the years, Stephen has worked in several countries and has many friends from other far less open-minded places than the UK. Knowing them has made him realise how important it is to have relatively safe and liberal cities like London.

However, the recent rise of the conservative far-right across the globe upsets and worries him. People are becoming dehumanised by the press, and hate crime is on the rise. He worries that things will go back to how they used to be. "If London loses its wonderful liberalness, where will people like me go to feel safe?"

Stephen holds a photo of himself and Richard at their civil partnership ceremony at Clapham Common.

VITO Ward

Vito was born in 1943 in the mining village of Prudoe on the banks of the River Tyne in Northumberland.

She spent her early years in the family’s two-bedroom council house with its coal shed and WC in the garden.

Vito could have done better at school. Back then, educating women wasn’t taken that seriously. Like most people in the village, her horizons didn’t extend beyond working in a factory or a shop.

She left school at 15 and got a job at a grocers. She scrubbed the floors, cleaned the windows, and weighed the produce. She got £3 and thruppence per week.

Like all teenagers back then, she liked rock and roll music. She and her friends would hang out in the village coffee shop listening to the Juke Box while trying to make a glass of Coca-Cola last as long as possible.

Vito always felt a bit different from her peers. When they talked about boys, she knew that she didn’t feel quite the same as them. She had boyfriends, but it never felt right for her.

At the weekend, she would go to dances. The girls always got there first and danced with each other while waiting for the boys to turn up from the pub. Vito was always a bit disappointed when the boys arrived.

She knew that if she wanted to broaden her horizons, she had to get away from the village.

She saw a leaflet for the Wrens (Women’s Royal Naval Service) and loved the pictures of the women in their blue uniforms driving trucks, doing sports, horse riding, and rifle shooting—she thought, “That’s the life for me.”

Her mum was terrified at the thought of Vito joining the military. She was dead set against the idea. Fortunately, her dad was more supportive, so Vito applied.

Vito still remembers that day in January 1961, waving at her mum, who was crying on the Newcastle station platform, as she headed off on the train to London. She had to cross the capital to Paddington and get another train to Burghfield in Reading. It was here that she and some other recruits were met by a Wren in uniform driving a ’Tilly’ truck (Utility vehicle)

At the training camp, there were girls from all walks of life. There were about 20 in her division. Vito made friends with a very posh girl training to become an officer. She was much more worldly than Vito and helped her settle into her new life in the military.

Vito loved being in the Wrens. The camaraderie appealed to her, and she felt she had a real sense of purpose for the first time in her life.

Vito started as a steward, working in the catering department, serving meals, washing dishes and cleaning tables.

She would much rather have been a driver like the girl in the leaflet, but she didn’t have a license, and because of her lack of education, her options were quite limited back then.

However, Vito was keen to learn. The Wrens had an education department, and Vito started taking lessons and quickly rose through the ranks.

It no longer mattered that she could have done better at school as she had a lifelong career ahead of her.

Vito ‘played the game’ like everybody else and had boyfriends. She was intimate with female friends, but it was never sexual; she wouldn’t dare risk taking it further in case she was wrong.

It wasn’t until 1965 that she met another girl on the hockey team who invited her for a weekend at her parents’ house in Dorset. They shared a bedroom. Sharing beds with friends was the norm back then because nobody had enough bedrooms. But that night, ‘things just happened’, and it felt like the most natural thing in the world to Vito.

It was a secret, and neither would dare tell anyone; back then, being gay was never talked about, so they thought they were the only ones.

Not long after, Vito was introduced to the Horse & Groom Pub in Southampton. It was one of those pubs that accepted people who, back then, were not allowed in other pubs: West Indian Sailors, gay people, prostitutes and women who dressed as men. Being in the pub opened up the world for Vito. She’d finally found a space where she could be herself without the fear she experienced up until then. She would get changed in the car before going into the pub, and she still remembers how excited she felt being in there with a girlfriend and being able to relax.

The Horse and Groom pub in Southampton. Demolished in the 1970s.

She learnt the subtle ways that like-minded women used to identify themselves. There was a particular language. In conversations with a new person, one might mention somebody who was known to be gay and say, “Do you know such and such? She’s a very good friend of mine.” If the person responded, “Oh yes, I know her, and do you know so and so?” one would get a pretty good idea of the person’s persuasion without overtly saying anything.

Some women also wore onyx pinky rings to identify themselves as lesbians. However, this wasn’t foolproof, as some straight women wore them anyway.

According to Vito, being a lesbian back then was like being in a secret society; “There was a whole group of us from all walks of life, living this quiet life undercover, all the time hoping that you would never get discovered.”

Vito also used to visit the Robin Hood Club in West London. Again, she would dress up and put a long coat on to cover her clothes or would get changed in the car outside the club.

Not only was being gay strictly forbidden in the military but it was also frowned upon by society in general. Openly gay people often risked abuse both verbally and physically in those days.

Vito had to keep the whole thing a secret. For example, while stationed in London, Vito shared digs with another woman and became close friends. It was only afterwards when she was transferred to another part of the country, that she discovered that her flatmate was also gay - neither had dared to tell the other as they were both pretending to be straight.

Vito excelled in the Wrens. She consistently scored highly on the assessments and saw herself having a long and successful career in the Navy.

By this time, she had served for nearly ten years and had risen to the rank of Petty Officer, a highly respected role. She was in charge of the household, had her clothes laundered, and was addressed as Ma’am by lower-ranking Wrens.

She was due to be promoted to get her ‘Chiefs buttons’ (Becoming a chief officer), and assumed that this was why, one morning, she was called in to see the officer in charge.

However, as soon as she entered the office and saluted the officer, the charge of being a homosexual was read out to her.

A woman she had dated had been caught, and when the officers went through her things, they found some letters from Vito. Vito had always been careful when writing never to use people’s full names, so she knew that although the letters were incriminating, they didn’t prove anything. However, when she was directly asked if she was a homosexual, she couldn’t bring herself to lie and told the truth.

She was informed that this was against ‘The Naval Discipline Act’ and that she was to be discharged and had to hand over her Wrens hat.

In that one meeting, Vito lost everything. After nearly ten years of military service, she suddenly found herself standing on the street with her box of possessions. Her career, accommodation, and everything she had worked for was gone. It was such a shock that Vito felt numb.

She had a few savings and found a bedsit in Earls Court but had no income, pension, or support. She’d been in the Wrens since 17, so she was utterly unprepared for civilian life.

She was too ashamed to explain to her parents what had happened, as she hadn’t yet come out to them.

Being in ‘a secret society’ meant that Vito knew gay people from all walks of life. Everyone in the group was very supportive and helped her through this difficult time.

Eventually, Vito managed to get a job looking after a large serviced apartment block in Pimlico that came with its own flat. She was responsible for the upkeep of the apartments where some very well-to-do and influential people lived. Ironically, the commanding officer of The Wrens lived there, and Vito came in contact with her on several occasions. The woman had no idea that Vito was gay.

Despite having what she thought was a lifelong career in the Navy abruptly cut short, Vito managed to get back onto her feet and has always worked and found success in various jobs. However, when she was in her late thirties and training to be a social worker, she had a breakdown.

She went into therapy and discovered that this stemmed back to her losing her job in the Wrens.

At the time, she was so busy trying to survive that she never processed the shame and anger she felt about the unfairness of her military dismissal.

Psychotherapy sessions helped Vito come to terms with this. This started her interest in the subject, and she went on to train to become a therapist herself.

Vito is now an active 81-year-old. She swims, plays badminton and enjoys yoga. She sings in a choir and recently cycled 500K through China to raise money for the landmine clearance charity MAG.

She is a member of the charity “Fighting with Pride”, an organisation that campaigns to get recompense and apologies from the government for LGBT veterans who were unfairly dismissed because of their sexual orientation.

Right up until 2002, when the military finally acknowledged the rights of its LGBT service men and women, many were forced to leave the service. Not all were as resilient as Vito and able to rebuild their lives. Some became homeless, and others even committed suicide.

In 2022, then-Prime Minister Rishi Sunak finally apologised on behalf of the Government, but the promised compensation still hasn't been paid. Vito served for nearly ten years and deserves the pension she would have received if she had remained a Wren.

Vito loves her neighbourhood in SW London and is the founder of a local LGBTQ+ coffee morning for over 50s. It was one of the first in London to cater to older members and has inspired several others to spring up around the country.

Vito also organises a yearly Street Pride in her neighbourhood. Many local people joined in, and it’s a great way for everyone in the community, no matter their sexual persuasion, to get together.

To Vito, one of the joys of being a lesbian is that it has given her the opportunity to meet people from all walks of life and from all over the world. It’s a club that Vito is proud to be part of and that, thankfully, in this country at least, isn’t secret anymore.

Gina

Gina's childhood looked ordinary from the outside, but she never felt quite right inside. She couldn't explain it; it was just a sense of unease. She behaved no differently from the other boys, but whenever she saw an elegant woman, she'd quietly think, Why can't I be like that?

Her obsession was aeroplanes. At 16, she left school to join the RAF, hoping the military might "make a man of me." She trained as a storeman, bought a motorbike, hung out with the lads and even had a girlfriend. The structure helped her bury feelings she didn't yet understand.

In 1970, she was posted to Germany. She loved her time there as she found a small group of servicemen who weren't the usual macho types. Some were clearly gay, though it was never spoken of because discovery meant court-martial. With them, Gina felt at ease.

In 1973, two of those friends left the RAF and moved to London. When Gina was posted back to the UK, she'd visit their flat and go to bars with them. She didn't know if she was gay herself. She was simply trying to work out what she felt.

Eventually, she couldn't bear the double life. Despite having just been promoted to corporal and knowing she could end up in Colchester Military Prison, she told the medical officer how she felt. Within a month, she was discharged as "below current medical standards." Losing her RAF career hurt, but the relief of not having to hide was stronger.

She moved to London, got an office job and went out on the gay scene. It felt freer but still not quite right. The feminine feelings didn't fade. She had a few encounters with men, but sex was never central to her life.

She loved music, spending nights watching bands like The Stranglers before they were famous and her personal favourite, Meal Ticket. At a venue, she met Jan, a BBC production assistant. They married in 1979.

They were happy, but living with a woman full-time intensified Gina's suppressed feelings. When Jan was away, Gina would try on her clothes. The guilt was awful, but it felt amazing to finally express something she had buried for years. She began buying her own clothes and hiding them in the loft, knowing Jan's fear of spiders meant they'd never be found.

Jan's career flourished. Gina worked as a distribution manager. They had good jobs and a solid marriage.

At 40, they wanted a change. They sold the house, quit their jobs and took on a country pub. It was fun until the 1990s recession wiped them out. Years followed as relief pub managers across the country. It was a nomadic existence, but they stayed strong as a couple.

Eventually, they settled in Horsham. Gina then worked for an aviation supply company, which rekindled her love of aircraft. The arrival of the internet changed everything. She realised there were others like her. Repression became harder. The secret wardrobe grew.

In 2006, after a drunken night on holiday in Greece, Gina blurted out the truth. Jan was devastated. They had counselling and agreed not to mention it again. But the compulsion never left. When the opportunity arose, Gina would sneak home for 'a dress-up session.'

In 2014, Jan developed a cough that wouldn't shift. It was stage four lung cancer, and sadly, she died soon after. Ten years have passed, but the grief is still raw for Gina, and she broke down recalling this.

At 65, she had no one left to hide from. About a year after Jan's passing, Gina began attending trans support groups and adjusting how she dressed.

She saw her GP in 2016. The NHS waiting list dragged on for years. On her birthday in 2022, she was finally told the surgery could go ahead.

Gina chose the cosmetic option rather than fully functional surgery. At 73, it was less risky, and sex had never been a priority.

In 2023, she made the slow walk to the operating theatre, filled with excitement and terror. When the bandages came off, it was, in her words, "a bloody mess." But emotionally, she felt complete. She had finally become herself.

Two years on, she feels whole. The grief for Jan remains, but Gina now lives openly and is a part of the community. She helps at the food bank and the pensioners' lunch club, and is a member of the W.I.

Her love of aircraft never faded. She has a flight simulator in her spare room. She collects model planes from her RAF days, reminders of a lifetime ago, when she lived another life.

Gina collects model aircraft and also has a flight simulator.

stephen

Sir Stephen Wall GCMG LVO is a retired British diplomat. He served as Britain's ambassador to Portugal and as the UK’s Permanent Representative to the European Union. In a 35-year career with the Foreign Office, Stephen was posted to Ethiopia, France, the US, Portugal and Belgium. In Whitehall, he was Private Secretary to five Foreign Secretaries and worked for three Prime Ministers (Callaghan, Major and Blair) in 10 Downing Street.

Stephen was born in Croydon in 1947. His mother was a Catholic, and he was sent to a local convent school from the age of four. His first confession was when he was just five. He remembers being shown pictures of souls being prodded by the devil in hell and was told that more or less anything enjoyable was a mortal sin.

When he was 8, he was sent to St Richard's, a Catholic all-boys boarding school in Malvern, Worcestershire.

It was a strict environment, but he got an excellent education. His teachers had him reading Shakespeare at 11 years old. He remembers school trips to nearby Stratford upon Avon, where he saw Charles Laughton play King Lear and Michael Redgrave as Hamlet.

He had a mixed time at school. He was hopeless at games and was one of those unfortunate kids who were often on the receiving end of "De-Bagging" (Having your trousers and pants abruptly pulled down without your consent).

Six boys shared a dormitory. One night, when Stephen was around ten years old, he awoke to discover that another boy had his hand inside Stephen's pyjamas and was feeling his genitals while kissing him on the mouth. Startled, Stephen said, "Stop", and the boy ran back to his bed.

However, afterwards, Stephen realised that he had rather enjoyed the experience and asked the boy if he would do it again.

This never happened, but the incident made Stephen feel so guilty when his parents visited, he confessed to what had happened.

His dad marched straight to the headmaster's office and reported what had been going on at the school.

Stephen was questioned by the headmaster the next day and made to name names. The headmaster summoned the other boy, who denied it. When the story came out that Stephen had snitched on a fellow pupil, nobody would talk to him, and his life became a misery.

Even now, almost seventy years later, Stephen feels that the meeting with the headmaster and becoming the school pariah were probably the most traumatic things that have ever happened to him.

The result was that Stephen shut down. He buried all thoughts of sex and was so mixed up, and cowed by the Catholic Church’s threats of hell fire, that he didn’t start to masturbate until he was 16.

Stephen was by then attending a Roman Catholic boarding secondary school, from which he secured a place at Cambridge University to study French and Spanish. At university, Stephen made one attempt at dating a girl because he thought he should, but he was relieved when she turned him down.

When he was 21, he applied for a job at the Foreign Office. This was during the Cold War, and there had recently been several scandals where government officials were blackmailed by the Russians who had discovered that they were gay or having affairs.

As part of the vetting process, two retired policemen interviewed Stephen, and they asked if he had ever had any homosexual experiences. Stephen immediately confessed to the incident at school. When he went on to tell the policeman he was just ten at the time, they laughed it off. They then asked if he had any homosexual tendencies, and Stephen said no.

He knew by then that he was attracted to men but couldn't believe or accept that he was gay. To Stephen, being gay was such a sin that he desperately tried to convince himself that perhaps his feelings were down to the fact that he just hadn't met the right woman yet.

Stephen got the job. The interview had made it clear that being gay was not acceptable in any shape or form, so as a good Catholic, he continued to repress his feelings.

After overseas postings in Addis Ababa and Paris, Stephen met Catharine, a secretary at the Foreign Office Press Department. Stephen took her out to lunch, and they became a couple. They married shortly after and remained together for 39 years. Stephen believes he genuinely fell in love with Catharine, and being with her made him determined to conform and defeat all thoughts of men.

On the surface, it was a successful marriage. The couple had a son, Matthew, and Stephen's career went from strength to strength. In the early 80s, they lived in Washington, where Stephen worked in the British Embassy.

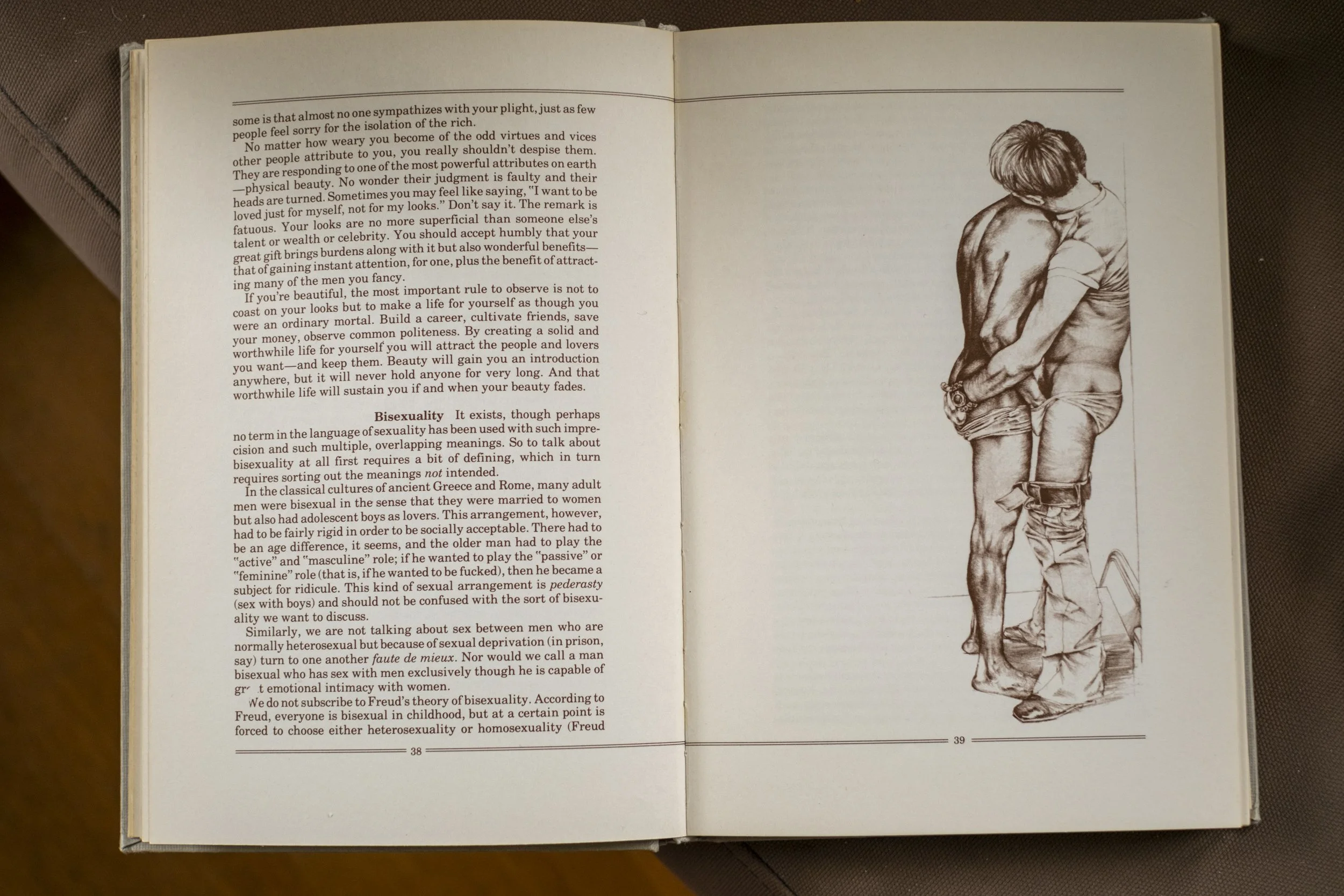

Stephen regularly went to Mass; he threw himself into work and family life and had more or less managed to suppress his feelings. But, one day, in a Washington bookstore, he came across a book called The Joy of Gay Sex.

That such a book could even exist was a revelation. In it, all the things Stephen had been brought up to think of as shameful were depicted as perfectly normal for men who were attracted to men. Within the book, he saw a picture that stopped him in his tracks. It was a simple pencil drawing of two topless men kissing and fondling each other. The image encapsulated Stephen's desires: everything he wanted to do but also everything that was morally, socially and, as a committed husband and father, inadmissible. He knew that he shouldn't, but he bought the book.

‘The Joy of Gay Sex’ by Dr. Charles Silverstein and Edmund White.

When he was back working in London, he became friends with a co-worker, and they often went on hiking holidays together. As Stephen spent more time with his colleague, he gradually fell in love with him. He admits that he was besotted. Stephen didn't dare do anything but felt that if the friend had made a move, despite all the pain it would cause, he would sacrifice his marriage and career so they could be together.

Nothing happened; the co-worker was straight. But a short while later, Catharine discovered that Stephen had a drawer full of photographs of his colleague. They were just ordinary snapshots, but the fact that they were hidden in a drawer made her suspicious.

She confronted Stephen and asked him if the pair were lovers. Stephen truthfully replied that they were not.

Perhaps this was the time to tell Catharine about his conflicting feelings. However, he loved his son, and he loved Catharine. If the truth came out, his career would be ruined, and there was never going to be a relationship with the man. So Stephen decided not to confess. Instead, he resigned himself to the fact that being with a man would be something unattainable for the rest of his life.

Stephen threw himself into his career and often worked 80-90-hour weeks, ensuring he had no time to think about anything else.

However, when he retired at 60, not having the distraction of work suddenly meant his internal pressures started to mount. He had time to reflect on the conflict within.

Around this time, Stephen went on a holiday with his brother-in-law, whose wife had recently died. When Stephen returned, Catharine had found some gay magazines hidden in the house. These were not pornography, but they were aimed at a gay audience.

When she confronted him, Stephen heard himself, for the first time, saying the words out loud, "I think I've known all my adult life that I'm gay."

Initially, Catharine was more hurt than angry. It was a tough time, and Stephen still feels awful when he remembers the look on Catharine's face. However, the relief of saying out loud that he was gay was immense. To Stephen, finally being true to himself and, at last, being honest meant everything. It was, in fact, even more important than the prospect of being able to have a male partner.

Catharine wasn't keen on everyone knowing that her husband was gay, so they decided to tell only Stephen's sister, who wasn't surprised, and their son, who was around 30 then. His reaction was, "Dad, it's cool to be gay."

Stephen and Catharine remained together for a further five years. The understanding was that Stephen would have to be discreet about his sexuality.

However, word eventually spread, and the couple divorced. Catharine stayed in the family home, and Stephen moved into a nearby flat.

After being married for so long, Stephen was suddenly single. Through the dating site Guardian "Soulmates," he met Ted, a retired consultant at Great Ormond Street Children's Hospital in central London. Ted was six years Stephen's senior, and his story, like Stephen's, was also one of conforming due to the attitudes towards being gay back then. Ted had also encountered another boy at school, met a girl at university whom he married, and thought he "was cured".

Once his marriage inevitably ended, Ted spent 25 years living with his long-term partner Peter, who had died about a year before he and Stephen met on the dating site.

The first date between Stephen and Ted was in The Marlborough Arms pub off Tottenham Court Road in central London. Stephen was immediately attracted to Ted. He was tall, distinguished-looking, and had a lovely smile. Once the evening ended and they were saying goodbye, Ted kissed Stephen; it wasn't a passionate kiss, just a peck on the lips. As Stephen walked home, he thought, "Is this what I want?" It didn't take him long to answer his question, "Yes, actually, it is."

They became a couple, and this was a joyous time for Stephen. At last, he felt complete. He was in love.

He had loved Catharine. (They remain friends). His love for Ted made him feel whole because it wasn't based on Stephen having to deceive himself and others. For the first time, he was comfortable in his skin.

Ted and Stephen were together for seven years. They each remained living in their respective flats but saw each other all the time. They travelled extensively and even crossed the Atlantic on the Queen Mary. Despite being one of the country's most eminent anaesthetists, Ted had a sense of humour. During the voyage, he got someone on board to film him and Stephen recreating the famous Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio scene from The Titanic.

The pair married in 2019 at Marylebone Town Hall. At last, Stephen felt complete. However, a few years into their marriage, a cancer that Ted had previously been treated for returned. Eventually, it spread. Being in the medical profession, Ted knew immediately that this was serious. He and the oncologist who treated him thought that he'd have another six months to live, but the reality was that he only had a couple of weeks.

Stephen and members of Ted's family were present when he died at home in London.

They'd only had seven years together, but each remains precious to Stephen. He still misses Ted terribly. Recently, he was wandering around a hotel garden where he and Ted had previously stayed. Upon seeing a particular plant, Stephen turned to say something to Ted, but of course, he wasn't there.

At 77, Stephen has missed out on so much due to having to hide his true self for most of his life. He didn't kiss a man until he was in his mid-sixties. It wasn't until his late sixties, when he met Ted that he had a short-lived but incredibly loving relationship with someone who knew Stephen for who he really was. Indeed, shortly before his death, Ted said to Stephen: 'I think one thing I've done for you is to enable you to fully embrace your sexuality.'

Stephen is pragmatic when it comes to how his life has turned out. Had he admitted he was gay when he was young, he would have been expelled from school, his parents might have disowned him, he would never have had his career, and he would never have had a wife he loved, his wonderful son or indeed his grandchildren, one of whom was a ring-bearer at his wedding with Ted - The world has changed a lot since Stephen was his grandson's age.

Allana

Allana knew she was different from the age of four. She loved to dress as a ballerina and was often teased at school.

When she tried to tell her parents that she felt she was in the wrong body, she was told to “stop being soppy” and was clipped around the ear. As she grew older, the clip became a beating, but Allana couldn’t help how she felt.

Eventually, after years of bullying, Allana retreated into herself. She became isolated and lonely and decided to conform.

After working briefly as a butcher’s apprentice, she joined the Royal Navy as a steward. Around this time, Allana married and had a daughter, but nothing felt right.

She went on to become a Navy diver. Being underwater gave Allana a sense of inner peace. The noise that had constantly sounded in her head abated, and she felt calm and relaxed. However, being in the Navy meant she rarely saw her wife and child, so she left and tried to make a life for herself on the outside.

That didn’t work out at all. Her depression became so severe that once, during a parachute jump, she decided not to pull the cord. She wanted to die. It was only in the final moments of the descent that she lost her nerve and opened the parachute. She broke both legs from the impact.

The marriage ended, and Allana then enlisted in the Army. She was posted to Northern Ireland during the height of the Troubles. She was badly injured during an IRA ambush and ended up in the hospital. It was there that she met her second wife, a nurse, and went on to have four children with her.

Discharged from the Army, Allana decided to further her education. She got two degrees and started working as a social worker.

However, her life was still chaotic, and she was depressed much of the time. Secretly, when nobody was in, she started dressing as a woman. It felt good, but came with mixed emotions and a heavy sense of guilt.

This marriage also ended, and Allana decided to live alone. She began spending more and more time dressed as a woman. At first, just in the house, but eventually, she plucked up the courage to head outdoors.

Being a social worker was often stressful, and this was taking a toll on Allana. She was spending all day helping other people but never herself, and eventually this became too much, and when she was 63, Allana had a heart attack. That near-death experience was her wake-up call and made her decide she had to live the rest of her life as the person she had always known she was.

Unfortunately, Allana discovered that NHS waiting lists for gender reassignment were incredibly long. She was told that she would have to wait several years just for an initial assessment.

She had received a war pension due to her injury in Belfast, so she decided to self-fund the operation. Paying privately in the UK can cost upwards of £50,000, so Allana began to explore clinics abroad. Many wouldn’t take her because she was over 50, but eventually she found a highly recommended clinic in Bangkok, Thailand.

The first operation didn’t go as planned, but the second was successful. That was in 2016, and according to Allana, that’s when her old self died and her new self was born.

Allana believes that if she had waited for the NHS to treat her, she wouldn’t be here now. She feels she wouldn’t have been able to cope with the depression caused by gender dysphoria and would probably have ended her life. Several other people in similar situations have committed suicide while waiting for treatment. They just couldn’t manage without support and acceptance.

Allana reads the newspapers. Nine out of ten stories about transgender people are negative. There is no empathy, no positivity, just resistance. “People think it’s a fad. How can it be? I’ve spent just short of 70 years struggling. I’ve been beaten, I’ve been attacked, I’ve been rejected. Becoming who I truly am has been, in short, nothing but hard, hard work.”

Now aged 71, she feels happy and complete for the first time in her life. Her depression has disappeared, and finally, the calmness she once only felt underwater is now a permanent fixture in her life.

Michael Hewitt

Michael was born on a council estate on the edge of South Belfast.

His dad worked in a bacon factory during the day and, to earn extra cash, at the telephone exchange at night.

He had an 'okay' childhood. They were an ordinary working-class family and never had much money, but neither did anyone else, so Michael was unaware of it.

As a small boy, his big treat was getting a coconut bun from the baker's van that came to the estate every Saturday.

He did well in junior school and got into an all-boys grammar school. He remembers one of his friends hating the place because there were no girls, but this never bothered Michael.

He never really knew when he first became attracted to boys, but he remembers having no idea why his friends always talked about girls.

He loved watching wrestling, and when his parents were out, he would always look for pictures of boxers in the stack of old newspapers that his dad kept in the shed. It was a secret, and he'd never tell anyone.

When he was 16, he took the bus to a Bible class every Sunday. It was full of girls, but he never really noticed them.

Michael got three A levels and a place at Stirling University in Scotland to study English. His results meant that he could have studied at Queens University in Belfast, but he wanted to get away from home to have a fresh start and become more himself.

University life wasn't quite the liberating experience that Michael had hoped for. Stirling was a brand new university, and his course was tiny.

He lived in digs with six men, and in the next house, there were six women. Some of his new mates and the women became couples, and Michael was friendly with them all, but he never got intimate with anyone.

This wasn't uncommon in those days; it may have been the swinging '60s, but many young people were still so innocent and naive. He remembers going on a camping trip with one of the couples and a female friend. All four slept in the same tent together, but nothing happened.

Michael still wasn't sure if he was gay or not. In places like Stirling, it hardly existed as a word back then, and Michael thought that perhaps he was just a bit shy.

There was another girl with whom Michael was friendly. He remembers visiting her digs and getting himself drunk in the hope that if he had sex with her, then perhaps he would find himself attracted to women. However, it turned out that she wasn't interested in him anyway.

After graduating, Michael went to London to spend a year doing a post-grad at a library school.

He shared a flat with a guy from Nigeria. He was a lovely guy, and at this point, Michael confided in the Nigerian that he was gay. The Nigerian guy, who was straight, had no problem and wasn't phased about it at all. Just saying the words, 'I'm gay' out loud to someone was a massive relief for Michael. However, while studying in London, he wasn't intimate with anyone.

After finishing the course, he returned to Belfast and got a job working in the film library for BBC Belfast, where he remained for 14 years.

There were a few gay guys at the BBC, but mostly, they were 'camp and out', but Michael just wasn't attracted to them. "I was afraid of the gayness."

There was only one gay bar in Belfast, and for the same reason, Michael didn't dare go there. Also, Belfast is a small city where everybody knows everybody. His dad was very religious and went to a church nearby, and Michael was terrified that somehow, he would find out.

Finally, when he was 31, Michael got reacquainted with an old university friend. They were on a holiday together in a caravan park. They ended up in bed, and neither knew what they were doing. Despite the initial clumsiness of the encounter, it felt so natural to Michael. Over the next eight years, they visited each other occasionally but were never a proper couple. Eventually, the other man ended the relationship.

By then, Michael was living in a house in the suburbs of Belfast and for the following years, he had no physical contact with anyone. Someone gave him a cat, which he called Frank, and that was his soulmate.

There was a fantastic job opportunity to be the Head of Libraries at the BBC Belfast. Michael was more than qualified, but he didn't have the confidence to apply.

The BBC also offered two years' pay for anyone taking voluntary redundancy, which Michael accepted. He used the money to buy a gift shop. Unfortunately, this didn't work out, and Michael nearly went bankrupt.

He came down to London and got work as a courier.

Despite London being so much more open-minded than Belfast. Michael couldn't connect with the gay scene; "I was too ashamed and just too shy."

He ended up living in Tooting in South West London, renting a room from an openly gay man. He was younger than Michael and very worldly and confident. He would often bring people back to the flat and, on several occasions, came onto Michael, but he just wasn't interested; Michael was looking for more; he wanted a partner.

After seven years of living in the flat, Michael's landlord sold up, and Michael had to leave. By then, he was in his mid-fifties, and because he also had a heart condition, he got a council flat.

By then, Michael was feeling a bit more confident. He invited a man back to his new flat who was very open about his sexuality and quite a loud and flamboyant person. One of Michael's new neighbours spotted him, and she told everyone on the estate, 'There's a poof living there,' making Michael's life a misery.

One of the neighbours was a heavy drinker, and she would stand with her friends outside Michaels's flat, hurling homophobic abuse at him in the early hours of the morning. She had a big family, and one of her teenage sons would mock and threaten Michael.

Eventually, this became unbearable, and Michael reported it to the Housing Officer. The housing officer said that the family was known to the council and, for his safety, offered him a new flat in Tooting. "This was wonderful; I felt safe."

Michael has always been a religious man, and the way his neighbours treated him on that estate still angers him. To him, being gay is no different than being born left or right-handed - it's predecided in your mother's womb.

"I had no choice whether or not to be gay; I was born that way, but people can decide whether or not to be decent and understanding of others."

Michael has a friend who visits some weekends, but his friend doesn't want a relationship, just casual sex. Michael wants a companion and someone to love. Michael is still looking for that soulmate. He hopes that one day he will find him.

A few years ago, after his mum died, Michael's dad went into a care home. Michael would visit and take him for a drive to the graveyard where his mother (Michael's grandmother) is buried. The cemetery is in beautiful countryside with the Mourne Mountains in the background.

After visiting the grave, they sat in the car admiring the view. His dad said, "Is nobody out there for you, son? Can you not find a wife to give me grandchildren?"

It was the perfect moment, but Michael couldn't bring himself to tell him that he was gay. Perhaps if he'd found love and had a long-term partner, things would have been different, and he would have come out to his dad. He never did get the opportunity because his dad passed away two years later.

Michael isn't a big fan of online dating. He said that there are a couple of sites that are okay, but he doesn't want hookups for sex. Michael wants love. He's still waiting, and he's still hopeful.

He recently saw a photo of two young men kissing and thought, "You are lucky so-and-so's being able to do that."

In Michael's words, "I was always so frightened; nowadays, people can be whatever they want—and there isn't the shame. I'm not nervous about it, but you do start thinking about dying, and you realise there's just a limited amount of time left. I wish I had been born a bit later when things became much easier for people like me.”

Peter and David

Peter was born in London in 1936.

His parents had come to England from Italy in the 1930s. During the war, when children were being evacuated, Peter’s mum refused to have the family separated, so he stayed in London throughout. He will never forget the Blitz. His most vivid memories are of the constant sound of glass shattering as bombs fell, and the barrage balloons floating high above his street.

He played around a bit with girls, but his first sexual experience was with an older male neighbour when he was about 13. The fact that it was with a man didn’t bother Peter. Despite being raised Catholic and knowing both the church and the law would see it as wrong, it all felt entirely natural for him. He accepted who he was at a very young age.

As he aged, he discovered that meeting men wasn’t difficult, especially in public toilets, parks, tube stations, and certain department stores. He never told his parents. His father died when Peter was still young, and although it was never discussed, he feels his mother knew. Despite her being an Italian Catholic, she never pushed him to marry or have children.

Peter was always promiscuous and enjoyed the freedom of having multiple partners. He had no interest in settling down or getting into a serious relationship, but this all changed when he was in his 50s and met David.

David was born in rural Cheshire in 1950. Although he was a teenager during the ‘Swinging Sixties’, attitudes in his part of the world were still incredibly conservative.

He knew he liked men from the start, and when he was about 18, his parents discovered that he’d had a sexual encounter with another man. Seeing how appalled they were had a profound effect on David.

At first, David tried to convince himself he could change. He attempted to sleep with women, but it just didn’t work. Eventually, he decided it wasn’t worth the emotional toll. He pushed sex and relationships to one side and lived celibately for 20 years. He built a good life: a successful career as a chartered accountant and plenty of friends, but he didn’t think love or sex were things he could have.

Then, one day, his brother, who was 9 years younger than David, visited with a male friend, and David could immediately see that they were a couple. The realisation that his brother was an openly gay man gave David the impetus to come out himself. He remembers the exact date: 25th March 1990. He was 39 years old.

For the first time, David began going to gay bars. As he became more comfortable with the scene, a friend told him about The Backstreet—a leather bar in the East End, the oldest of its kind in London. It was there, in 1991, that he met Peter. They’ve now been together for over 30 years.

David loves Peter’s mind. “He’s fabulous. Kind, generous, and brilliant,” he says. Peter says, “We may have met in a sleazy leather bar, but we have so much in common. We both love gardening, classical music, and theatre, especially the works of Stephen Sondheim. We’re so compatible.”

“Neither of us was really looking for love,” Peter says. “The relationship just developed beautifully. And we’re very happy together.”

They plan to keep pottering on, side by side, for as long as they can.

Gilly

Gilly was born in 1954 in a remote part of Kent. Nobody lived within a mile radius, and nothing happened there. It was a pretty lonely childhood.

She was sent to boarding school at twelve years old. She was no longer lonely, but the experience wasn't especially pleasant either.

She hung around with four other girls, one of whom was a bully. This girl was mature beyond her years and picked on the other four girls. Gilly remembered often hiding in the toilets because she knew she was going to get hit if she came out. Boarding school was sometimes brutal, and Gilly didn't enjoy it much. However, she did well academically.

Just as school finished, her parents moved from the countryside to Central London, which, unsurprisingly, was great for 16-year-old Gilly. This was in 1968, around the time of the Summer of Love, and she used to love exploring Kensington Market, Carnaby Street and King's Road when hippy culture was in full swing.

One night, she and a friend were chatting about India. They got the I-Ching out (A kind of dice used to divine one's future). Once they threw the dice, it said, "The time is right to cross the ocean." So off they went to India.

They travelled by public transport across Europe, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and on to India.

Gilly loved India, which, thanks to The Beatles, was full of Westerners 'Looking for enlightenment', but after a while, all the smoking joints and sitting around talking about spirituality became a bit boring and pretentious to her. She remembered waiting for her boiled egg at breakfast one morning. As usual, the chillum was being passed around, and when it was put in front of her, she looked down at this dirty old pipe and thought, "I don't want to 'wake and bake' and spend all day getting stoned. I want to do things and see things." So she passed the pipe to the hippy beside her and set off travelling through India.

She travelled alone all over the country, which had a profound effect on her. Her love affair with the country remains, and she has returned many times over the years.

Back in England, she studied English at university in Exeter, then returned to London and lived in a squat off The Caledonian Road to the north of the city. She started working as a journalist. By then, she had another boyfriend who was a bit of a hippy' and wanted to continue the hippy dream of moving to Scotland to become a self-sufficient farmer.

However, by then, Gilly was getting tired of the alternative lifestyle and living in a squat. She wanted to do something with her life, and that included building a career and feeling more settled. Her journalism work was going well, so she got a mortgage and bought a flat. It was a three-bedroomed flat in a beautiful Victorian house in Archway in North London, and it only cost £23.500.

She began working for a publication called 'The Oilman, ' a business magazine for people in the oil industry.

Gilly enjoyed working in the business end of journalism as the writing style was more matter-of-fact and objective. Writing for the consumer press was, in her words, too 'fluffy' and chatty - a writing style that she liked less. She could have easily worked for women's publications but wouldn’t have enjoyed writing about make-up, hair, etc. Gilly was much happier writing more technical pieces about the design of a new oil rig, drilling method, or similar.

The job involved flying offshore to oil rigs in the North Sea by helicopter, and she spent a lot of time in Scotland, Europe, and America. It was exciting and always interesting work, which led to a job as a staff writer for a daily newspaper.

It was around this time that she met Julian. He worked in communications at an oil company. She liked him because he was straightforward and had. 'his feet on the ground.' Until then, Gilly had spent most of her time with alternative, new-age people. Some of this was great; it was an experimental, forward-thinking lifestyle and a license to do whatever you wanted. To Gilly, the concept of not being responsible for your actions sometimes felt too hedonistic and often selfish. So, meeting someone like Julian, who was more of a regular guy, was refreshing.

They had an Indian wedding in London. Gilly loved it, but to this day, she still has no idea what Julian thought about it. They did the typical couple thing: They had two kids and moved out of London to the commuter town of Tunbridge Wells. Throughout this, Gilly continued her work as a freelance journalist.

Their marriage was fine at first, but they started drifting apart after about ten years. Julian was too straight and set in his ways for Gilly. Although she was not a fully-fledged hippy, she was still an open-minded person and didn't feel comfortable living 'the suburban dream.'

Then, when she was in her early forties, the couple went to a murder mystery weekend and met a new group of people, including Zuleika. Zuleika was half Indian and half Singaporean, and immediately, something sparked between them. Gradually, she and Gilly started to fall in love.

The magnitude of this experience made Gilly realise it was the first time she'd ever properly felt this way about another human being.

She and Julian decided to divorce. This would have happened anyway, regardless of Zuleika, but she was probably the catalyst that brought things to a head.

Being with Zuleika was a wonderful time for Gilly. Their passion and connection were intense. Every second they spent together felt incredible—something she had never experienced before and hadn't felt since.

However, the reality of the situation was that Gilly had two kids and was in the throws of a divorce; Gilly believes that their love could have got them through this, but culturally, it was unacceptable for someone with Zuleika's background to be with a woman. Because of this, Zuleika could never commit fully to the relationship as she always fostered this fantasy that one day, she would conform and meet a man she could tolerate marrying.

Eventually, they realised they couldn't make it work, and they separated.

For the first time in years, Gilly was single. She assumed her next partner would be a man, but then she realised that she actually had the option of not doing that, and it felt wonderful. Also, her daughter was a beautiful but still very young girl, and Gilly didn't like the idea of a man moving into the house with her. So, she started a new relationship with Pam, whom she met online. It was lovely to have a companion, and she and Pam were very close. The couple lived with Gilly's kids, who were very relaxed and accepting of their mum's new partner. Unfortunately, Pam became unwell and was diagnosed with a rare neurological condition that affected her muscles. As the condition got worse, she had to go into a care home and then passed away. Gilly and Pam had been together for ten years.

By then, the kids had left home, and Gilly bought a new house in Balham, where she still lives. She has just got out of a relationship that wasn’t a happy one. She is now single again and loves it. She's had a tumultuous life but currently feels the happiest she has ever been. She feels settled and comfortable with herself and has a large friend group. She loves the freedom that being single gives her and now feels free to take on any opportunities that come her way. She is currently learning Hindi and enjoys her part-time work as a handwriting analyst and lectures on the subject for corporate groups.

She is also active in the women's rights movement. She feels that women's rights are being eroded again and does what she can to protect them where possible.

Gilly recently went shopping with one of her many friends, who told her that another mutual friend had just started a new relationship. Her friend said that she felt a bit sorry for them because of all the anxiety and stress that comes with this. Gilly completely agrees. She knows a friend can hurt you, but never as badly as a partner who gets to know you so much more. Gilly is in no rush to find someone new.

She feels like she's reached a point of happiness in life and that, at 68, she isn't too old not to enjoy it.

Gilly feels that she never had that moment in life when everything fell into place and she realised that she was gay. Life isn't that black and white to her, and there was no sudden awakening. She met someone in her early 40s and fell in love; that person happened to be another woman. To her, kindness and good humour in a relationship matter most.

Bill

Cliff Richard made Bill realise he was gay. When Bill was a boy, he saw the pop and screen idol in a film at the local cinema and found him incredibly attractive.

Bill was born in 1946 in a coal mining village in Northumberland. His dad was a miner and was killed in a pit accident aged 57.

It was a tight-knit community, and the church was the centre of village life. Bill was in the choir and served on the altar.

At 15, Bill had his first sexual encounter with George, a boy from the next village. Over 60 years later, Bill and George are still friends.

His first job was as a religious education teacher in Dinnington, a coal mining village outside Rotherham. He lived in a small flat above a parade of shops within walking distance of the school.

Because of his religious background, Bill had decided to repress his sexuality. However, being in his early twenties, his urges occasionally got the better of him, and he would visit a gay bar in the nearby city of Sheffield. On one occasion, while at the bar, he asked a few people to return to his flat, a short bus ride away. About 20 men turned up, and this small get-together quickly became a party. One of the neighbours came to complain about the noise and was appalled to see that it was all men.

A few days later, Bill was teaching when he was pulled out of the classroom to talk to the headmaster. The neighbour had reported Bill. The headmaster said he would give Bill a good reference but had to leave the school immediately.

Bill was suddenly unemployed. Dinnington was such a small community, and Bill knew he couldn't stay, so he phoned George, the boy he'd when he was young.

George was living in London, and he told Bill to come. By teatime that day, Bill had packed his case, taken the train to London and was in George's flat in Shepherds Bush. George had a partner, and Bill slept on the sofa.

The school gave Bill a good reference, and he managed to get another job as a teacher in Hackney.

Bill also discovered that after he was fired from his first job in Dinnington, the whole school refused to sing the hymn in the assembly to protest the unfairness of his dismissal.

Once he started his new job, he rented a room in Chelsea from one of the other teachers at the school.

In addition to teaching, Bill worked in the evenings as a barman at The Queens Head pub in Chelsea. (One of London's first gay pubs, which recently closed and is now a restaurant).

After work, Bill would walk home through Chelsea. One night, he stopped at a public lavatory to have a pee. As he left, a policeman put his hand on Bill’s shoulder and arrested him for "importuning for an immoral purpose." He was taken to Chelsea Police Station, where the policeman told Bill that if he pled guilty, he would get a small fine, and the matter would be closed. Despite being completely innocent - he genuinely had just gone into the WC for a pee, Bill agreed.

He only received a small fine but remembers avidly checking the local papers for the following weeks to see if his case had been mentioned.

Fortunately, it hadn't, but a few weeks later, he was summonsed into the headmaster's office at the school.

The headmaster and chairman of the school governors were in the office. They told Bill that they had received a letter from the Department of Education signed by Margaret Thatcher (then Secretary of State for Education) stating that Bill had pleaded guilty of importuning for an immoral purpose.

When Bill explained what had happened, the governor and headmaster were satisfied that there was no problem with Bill, and he was allowed to continue working.

However, a few weeks later, Bill received another letter from the Inner London Education Authority stating that he had to be interviewed at County Hall.

After being interrogated by a couple of bureaucrats, he was then sent to a psychiatric ward where he was put into a little room where he was made to listen to some strange sounds from headphones while scientists measured his responses on a graph. To this day, Bill has no idea what the test was trying to evaluate. Bill found the whole experience traumatic.

Eventually, he received another letter from the Department of Health stating that after a thorough investigation, they had decided that Bill was not a threat to society and that he could continue working.

Even today, Bill is angered by how the police lied to him. They told him that if he pleaded guilty, he would receive a fine, and the matter would be closed. The police knew full well the ordeal Bill would have to go through due to pleading guilty.

A couple of years later, Bill had another run-in with the police. He'd spent the day helping a friend move some furniture in a van, and on the way home, he was dropped off at the Colherne, a famous gay pub in Earls Court. It was late, and Bill arrived just as the pub was closing.

He was chatting with a few friends outside the pub when the police turned up and told everyone to disperse. This was a common event at gay bars even though non-gay pubs in the area had similar crowds at closing time and never got any police attention.

The police stood around their van, shouting homophobic insults at the pub-goers and telling them to leave the area. Bill shouted back, "Why don't you go and arrest some murderers instead?" The police grabbed Bill and threw him into the van, took him to the police station and charged him with being “Drunk and Disorderly". Having only just arrived at the pub, Bill was completely sober, so the following day in court, he pleaded not guilty.

At the court case a few weeks later, Bill represented himself and, thanks to the statement of his friend who was driving the van, was able to prove that he couldn't possibly have been drunk at the time of arrest. Bill also questioned the police who arrested him about why they were intimidating men at a gay pub in the first place.

Bill was found guilty, but he received a tiny fine. The magistrates knew that Bill was innocent, but if they found him not guilty, they would have to charge the police officers with lying in court, so they gave Bill the smallest fine possible.

A short time later, Bill was in the same pub when he was approached by a good-looking young man who asked if Bill wanted to go home with him. Bill agreed, but when he left the pub with the man, he was ambushed by three men who threw him to the pavement and poured a can of paint over him. This broke Bill’s front teeth, and he had to make his way home covered in paint.

Bill believes that the police set the whole thing up because he had humiliated them in court.

By then, it was the 1980s, and Bill had left his job at the school in Hackney and started working as a supply teacher.

He met a man in his local pub and fell desperately in love with him. Unfortunately, the man didn't feel the same way, and this unrequited love tore Bill apart. He started to drink heavily.

Many of the subsequent years Bill spent in pubs and bars are a blur, but he remembers one morning sitting in a pub in Soho and feeling terrible. He looked at his pint of beer on the bar and suddenly thought, "I've got to stop this."

He went straight to the A&E department of St Thomas's Hospital. The doctors said that there were no spaces available for Bill and that he'd have to try to come off the drink on his own. They gave him some injections to get through the withdrawal, and Bill went home.

The following weeks were tortuous for Bill, but he managed to remain teetotal.

Becoming sober after years of having his mind befuddled with alcohol thrust Bill into a major depression. As his mind was cleared of the effects of all the alcohol, he found that he couldn't cope with the reality of life.

He remembers sitting in his flat in Balham for hours, staring into the middle distance. "I never went out and just spent all day staring at nothing."

Eventually, he got so desperate that he went back to the hospital. He told them that he wasn't drinking anymore but that he was in mental agony.

The hospital got him a psychotherapist, which helped enormously. But it was Bill's sister who changed everything for Bill. She remembered how much he loved drama at school and told him to get into amateur dramatics.

Bill went to Balham Library and found out about The Southside Players. By sheer coincidence, at that time, they were having auditions to do a play called 'Billy Liar' - Bill auditioned and got the part.

Bill admits that he was never that good at communicating with people and he was still in a state from coming off the drink. But he loved acting because he was being a character and not being himself. The rehearsals helped him socially, too. They got him out of the flat and interacting with other people away from the pub.

This was 30 years ago, and since then, he has appeared in hundreds of plays for several different theatre groups all over South London. Bill feels that acting saved his life.

He's 78 now and admits that he's feeling his age and no longer acts as much as he did. He still loves the theatre and recently became passionate about ballet. As a young man, he had no interest in it whatsoever, but upon seeing The Nutcracker, he became addicted.

He goes alone to the ballet but has befriended the regulars—there’s a small, close-knit group that attends most performances. He recently bought a giant TV. He never watches the programmes but has friends over to watch ballet on DVD.

Bill is also a member of 'South London Gays', a group that meets once a month in Clapham pub - he even has the odd drink now and again.

In Bill's words, "It's been a chaotic life, but I suppose I'm reasonably content now."

Timothy

Timothy was born in 1949 in the west London suburb of Norwood Green.

He didn’t enjoy school. In Timothy’s words, “A whole lot of different people are all thrown together in school, and the only thing you have in common is that you are the same age.”