Still buoyant in her golden wings

Still buoyant in her golden wings is a line from Charlotte Brontë’s poem Life, which, for me, encapsulates the spirit found in the incredible women photographed below. Each had a resilience and enduring spark that, despite having lived long and eventful lives, time has not extinguished.

ANGELA

Angela and the greyhound that she rescued.

From the age of 3, art has been Angela Landels’ whole life.

In her twenties, she became one of Britain's top fashion illustrators.

Her work in the 1960s and 70s captured the vibrancy of the London fashion scene and was often featured in Vogue, Harper's & Queen and Tatler.

She regularly worked with brands such as Austin Reed, Aquascutum and Liberty. In later life, her paintings and book illustrations were highly respected and appeared in galleries worldwide.

Angela is now 88, and recently her eyesight has deteriorated. Because of this, she can no longer paint, which she finds "Heartbreaking".

Megan's racing name was "Wine Taverna Megan," and when she stopped winning, she was made to breed. She lived in terrible conditions until Angela rescued her.

The pair were heading home from a walk on Clapham Common when they kindly stopped to let me take this shot.

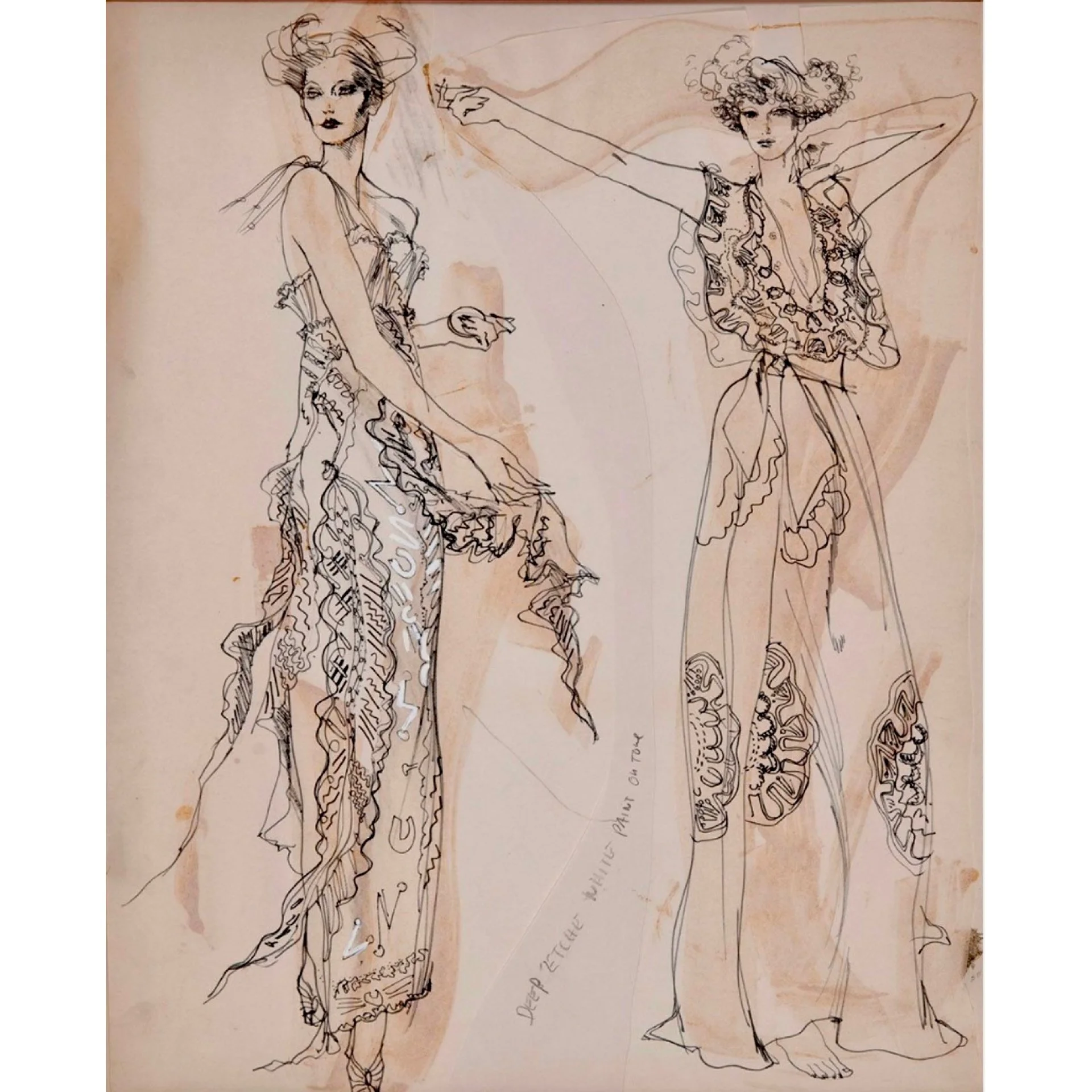

One of Angela’s illustrations for Harper’s & Queen.

June

June Barryford has lived in Soho for the last 35 years. Before retirement, she worked in publishing. She was born in Clapham but spent many years living in France which explained her slight accent. She was happy for me to take her photo and I loved the way that her blue scarf complimented the blue sky. When I asked June her age, she said ‘that’s a secret’. (Winner of Portrait of Britain 2021)

Ruby

Ruby was born in Bristol in 1935.

After leaving school, she worked in the catering business, but keen to broaden her horizons and gain her independence, she moved to London.

For most of her working life, Ruby was the personal secretary to the Chairmen of large corporations at various head offices in Central London.

After getting married, she and her husband Allen settled in Balham. At the time, Balham was affordable because, to most Londoners, it was considered a ‘South London backwater,’ her friends often teased her about living in the area. That was back in 1975, and Ruby is delighted that Balham has since become the vibrant and desirable place it is now.

Ruby worked way beyond the national retirement age and has always been a very active woman. She loves walking and, until recently, was a member of The Ramblers.

Allen passed away nearly 20 years ago, and Ruby still finds this difficult to cope with. She has to ‘fight hard’ to accept his absence. “He had many qualities and abilities, and I was fortunate to have married such a man.” After Allen’s death, Ruby volunteered at a local Hospice. This continued for over 12 years and formed an important part of her life after her loss. Unfortunately, the pandemic and the subsequent government restrictions put a stop to this. Ruby still remembers her days helping out there with much affection.

When I took this shot, Ruby was on her way home from her ‘falls’ class. A recent fall required a hip replacement, and the classes are helping her to recover.

Ruby admits that the accident has taken away some of her confidence. She knows her rambling days are over, but she is determined to remain independent for as long as possible.

According to Ruby, “One loses so many things with age, but you do gain wisdom. I’ve known many older people; they may not have been intellectuals, and they may not have had a grand lifestyle or anything like that, but their wisdom was infinite. It’s hope that comes with age.”

Ruby added that we all must accept life changes and shouldn’t keep looking back. Her adage is, “Go with the flow. Accept what you can, and discard what you can’t.”

RITA

Rita loves her headscarf, just like the screen idol who shaped her life.

Rita lives in the same house that she was born in. Her parents, aunt, and grandmother lived there. Now it's just Rita, and she's about to celebrate her 90th birthday.

She went to school around the corner and loved it. She left at 15 and got a job in a local photo studio in their development and printing department.

Film photography was huge in those days. Every town had studios where people could get their photos taken, and thousands were employed in the industry.

Unfortunately, the boss was "A bit free with his hands", but Rita had to put up with it to keep the job.

She then got a job at a different studio, and an 'old timer' who worked there taught Rita how to retouch photos by hand. The images were on glass plates. Rita learnt the fiddly job of painting out blemishes, whitening eyes and improving eyelashes. She's always loved painting and drawing, so she enjoyed this job.

Rita also enjoyed the theatre. Her aunt would take her to children's theatre and, as she grew, to musicals and more serious productions.

Rita loved Shakespeare. She's always been a regular churchgoer, and when she was small, the sermons were in Elizabethan English, making it much easier for her to understand Shakespeare.

The actors she loved the most were Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. She first saw them in 'The Sleeping Prince' at the Phoenix Theatre in London. Their performances had a profound effect on the then-20-year-old Rita. She went on to see all of their plays and films.

She much preferred the theatre to the cinema as to Rita. The contact between the actors and the audience was something special.

Through her theatre visits, she made friends and discovered that some would wait at the stage door after a production. Rita would never have done this alone, but because they went, she decided to join them. As Vivien Leigh left the theatre, she would always take time to talk to the fans. This was so exciting for Rita. At the time, Leigh was one of the most famous actors in the world, having won 2 Oscars for "Gone with the Wind' and, 'A Streetcar Named Desire.'

When Leigh was rehearsing for an Old Vic tour of Australasia at a theatre in Finsbury Park, Rita waited at the stage door with some flowers. When Leigh arrived, she was delighted with the flowers and invited Rita to watch the rehearsals. Afterwards, they chatted, and Rita told Leigh she would miss seeing her while on tour. Leigh gave her a list of all the addresses she would be staying at while away and asked her to write.

Rita did and was thrilled when the first postcard arrived from Australia. Over the following years, the pair wrote over 50 letters to each other right up to Leigh's death from TB in 1976 at just 53. Leigh's letters to Rita were often very personal. She was surprisingly open when she wrote to her fans.

After her death, Rita wanted to do something to help preserve the memory of Vivien, so along with her friend Joyce, she set up the ‘Vivien Leigh Circle’, of which she is still president.

The club grew and grew with more members joining; many younger members weren’t born until after Leigh's death.

The group regularly meets and goes on trips to see the places where Vivien lived and performed.

Rita donated all her correspondence and photos of Leigh to the V&A, which is held as part of the ‘Rita Malyon collection’.

Rita’s love of the theatre and Leigh has made her many friends and given her an insight into a world far beyond her suburban home.

Watching the 90-year-old enthusiastically go through her memorabilia, one can still picture that star-struck young girl from the 1950s.

Rita never married. She’s always had friends of both sexes but has never been attracted to anyone ’in that way.’

She still loves theatre and often enjoys the productions at the nearby Richmond Theatre. Nowadays, the West End theatres are a bit too expensive for her.

Despite having bowel cancer, she walks her dog, Lacey, daily. She doesn’t use a walking stick apart from hiking on her holidays in the Lake District.

When she’s out, Rita always wears her headscarf, just like the Hollywood star that shaped her life.

Vivien Leigh

JOAN

Joan used to faint at school. After this happened a few times, the doctor was called and said that she was anaemic. She was put on iron tablets and cod liver oil and told to stay at home. Joan wanted to go back to school, but the doctor said that she had to rest and that it didn't matter whether or not she went to school because she was just a woman. So, at 13 years old, Joan's education abruptly ended.

Jobs were scarce in the countryside, but at 15, Joan got work in a sports shop in the town of Lymington. She lived in the attic room above the shop and worked as a housemaid and in the shop itself.

Once a week, she got a half-day off and would cycle the 8 miles home to the hamlet of Bucklers Hard to visit her mum and dad.

She became friendly with a boy named Charlie, who worked in the local greengrocers. His mum liked Joan and said she could visit them instead of cycling home if it was raining.

Charlie didn't like working in the greengrocers, and one day, he cycled to Bournemouth to join the Grenadier Guards. He was too young to join, but they let him in because he was a 'tall lad.'

Joan and Charlie got married. By their first wedding anniversary, WW2 had broken out. Being a member of the British Expeditionary Forces, Charlie was sent off to France before the regular soldiers.

Joan enlisted in the ATS, the Auxiliary Territorial Service, the women's branch of the British Army.

She was posted to Northampton to do her basic training. She learnt to march 'square-bashing.' She was sent to Winchester and then York, where she worked as a cook for the army.

Meanwhile, over in France, Charlie got shot by an enemy aircraft on the way to Dunkirk. He was shot in the thigh. Luckily, the bullet didn't hit the bone. Joan still has the bullet. Charlie was at Dunkirk and was ready to board the hospital ship to take him back to England when it was bombed in front of him. He was eventually taken back amongst the flotilla of small boats that came to save the soldiers who were stranded on the beaches of France.

Joan loved the ATS. She loved the camaraderie and responsibility of it all, and she also loved all the cooking. She left when she got pregnant with their first daughter. Charlie went on to serve in North Africa and Italy. He survived the Battle of Monte Cassino in Italy, which cost Allied troops 55,000 casualties.

After the war, Charlie became a painter and decorator, and the couple had two more kids, Brenda and Nigel. They moved into their council house in 1962, and Joan still lives there today. Sadly, Charlie died of cancer at just 70.

Joan gets up at seven and has cereal or porridge every morning. She cooks her main meal from scratch every lunchtime and has something small in the evening. If there's nothing on the telly, she's in bed by 9 pm reading. Joan loves reading.

Perhaps it was the discipline of her time in the women's army, but Joan has always been independent and only gave up cycling when she was 85. Her house is immaculate, and she still bakes a cake every week. Fruitcake, sponges, or scones.

Her only regret in life is not finishing school. She would love to have had more of an education and to have run her own bakery. One of her five grandchildren is now a top patisserie chef (something he must have inherited from Joan). She also has six great-grandchildren.

Last year, Joan got a letter from a fellow member of the women's army - Queen Elizabeth, congratulating her on her 100th birthday. Next month, she will be 101.

Joan and Charlie

Stella

Stella has a great sense of humour. As I attempted to take her photo, she said, "Take your time and hurry up." She then told me in a whisper, "I'm 89, but don't tell anybody."

Stella came to England from Guyana in 1955. She enjoyed the journey across the Atlantic. It took two weeks, and every night, they would show movies in the lounge. On board the ship were families, single men and women and many children. Everyone was excited about starting a new life in England.

Her husband, Cecil, had already come to England. He was working as a carpenter and living in Tooting. Stella left their son with his parents until she got settled.

Stella wasn't sure about England at first, but her sense of humour helped her through those early years. A white woman once looked at her hands and said, "Oh, look at that. You wear a wedding ring just like us,” Stella replied, "We normally wear our rings through our noses but put them on our fingers before we get off the banana boat."

Stella and Cecil lived in a single room in Tooting. Cecil worked, and Stella trained to become a nurse. The couple also had a baby daughter called Wendy

Stella then sent for her son, but her in-laws had grown attached to him and wouldn't let him come. Stella joked that although many English people think that people in the Caribbean lived in mud huts, her in-laws had a big house with six bedrooms. They argued that there was no way they would send their grandson to live in a single room in South London. So Stella's son remained in Guyana with his grandparents and still lives there.

Once Stella passed her nursing exams, she worked in the infectious disease ward at St George’s Hospital in Tooting.

She said the hospital had a strict hygiene policy. You'd scrub your hands, go into the ward, put on overalls, and then scrub your hands again. There were no disposable surgical gloves in those days. You had to go through the same process on the way out. All the hand scrubbing made her hands sore.

The nurses were given castor oil cream to soothe their hands, but it had a strong smell that Stella was self-conscious about on the bus ride home. The whole time Stella was a nurse, there was never any cross-infection.

Stella's daughter Wendy became a teacher. When she was in her early fifties, she started to get stomach pains. Because she was so dedicated to her work, she wouldn't visit a doctor until the school holidays. When she finally went, it turned out that she had advanced liver cancer, and sadly, she passed away shortly after.

Wendy has five children who often visit Stella. Stella feels blessed that she has all her grandkids around her. When they leave the house after a visit, 'The silence is deafening.'

Cecil passed away in 2009. He loved gardening. He'd grow vegetables in the back garden and flowers in the front. Stella told me everyone was friendly on the road where she lived in Tooting. Back then, people were constantly popping in and out of each other's houses. Everyone grew vegetables and cared for their gardens. The neighbours would share plants and seeds.

During this time, Cecil planted two beautiful roses in the front garden. Now that she lives alone, Stella got the garden paved because it was too much for her to look after. She ensured that the builders left Cecil's roses untouched. Every summer, without fail, they always burst into bloom.

Stella has since celebrated her 90th birthday.

Sylvia

Sylvia was born in Calcutta (Kolkata) in 1918.

Her family were in the Jute trade, and her father ran the Calcutta office. She remembers having an enjoyable childhood in a big house. She and her brother lived in the attic nursery and were cared for by a Scottish nanny, Christie. Sylvia adored her pony Rufus, who loved eating bananas. The pair rarely parted. She seldom saw her parents, perhaps once a week for lunch. Her mum loved to socialise and play bridge. When the heat got too much, the family went to the Mount Everest Hotel near Darjeeling, where it was cooler

At the age of nine, Sylvia was sent to boarding school in Eastbourne. She missed her parents, but missed Rufus even more. This school was progressive, with a roller-skating rink and a gardening patch for each student. Sylvia loved swimming in the sea, riding horses on the Downs, and especially the art lessons. Her teacher, Ms Douglas, instilled in Sylvia a lifelong love of the arts. Ironically, around then, her horse Rufus was given to a family who moved him to England. Sylvia tried to see him again, but sadly, without success.

At 13, she did a domestic science course where she and the other girls learnt how to create 3-course meals from scratch, which they never got to eat as the finished meals were served to the staff. Sylvia's next boarding school was in Oxfordshire. During the holidays, she stayed with her 'wicked uncle' He was a bully and regularly beat his sons. The children all slept in a dorm and were looked after by a Chinese Amah.

When school ended, like many young women of the time, Sylvia did a secretarial course. Then, encouraged by a cousin, moved to London to attend the Chelsea School of Art. Sylvia loved Chelsea, made friends, and developed a passion for sculpture.

After finishing, she returned to India to visit her family and grew closer to her father. He bought her a dog, Paddy, and they'd go out walking together.

War was declared, so Sylvia remained in India. In 1942, she joined the Women's Auxiliary Corps. It was the first time women had ever served in the Indian Army. Her job was to collate intelligence reports before they were sent to high command in Delhi.

Once, there was a Japanese bombing raid. Unlike the other girls who hid under the desks, Sylvia continued working. The officer in charge saw this and, impressed, promoted her to Junior Commander. This gave her new responsibilities and a jeep to transport her to and from the base.

She was later posted to Fort William, where she was the only woman on the staff. On her first visit to the canteen, Sylvia sat at the first table she saw, only to be told she was sitting in the senior officer's chair. Fortunately, the officers saw the funny side of this.

On another occasion, she arrived at a military ball unaware of a uniform-only dress code. She wore a bright red ballgown sent to her by an American aunt. The other women were furious, but the men queued to dance with Sylvia.

Not long after, she got engaged to Archie. She loved how relaxed they were together and always made each other laugh. Archie was posted to France and was blown up in his tank. Sylvia was devastated and, 80 years later, still wears his ring.

After the war, she entrusted her dog Paddy to her father and returned to England to train as a teacher. During this time, her parents moved to Singapore. When Sylvia qualified, she followed them there to work at a teacher training school, where she set up the first-ever pottery course. Much to Sylvia's distress, her beloved dog, Paddy, was nowhere to be found. To this day, she has no idea what her father did with him.

She returned to London in 1961, shortly after her father died. Her mother bought a flat in SW London but then decided to live in a hotel in Kensington, so she gave the flat to Sylvia. She still lives there today. Until she was in her late seventies, Sylvia worked as a sculptor. Her expressive busts have been widely exhibited.

Sylvia is now 107. She has limited hearing and uses a stick, but her carer only visits twice a day to prepare her meals.

Sylvia was so patient as I photographed her. She was genuinely interested in the process, peering at the shots on my camera screen without needing glasses.

She enjoys the odd Jaffa Cake and drinks nothing but ginger ale, which she told me with a smile, is the secret to her long life.

Edna

History tends to talk about the London Blitz, but ports like Southampton, where Edna lived, were heavily targeted. Over 2300 bombs and 30,000 incendiaries were dropped on the city.

Edna remembers the sound of the bombs, the anti-aircraft guns and the shrapnel coming down. Her house had no garden, so their shelter was in the cellar. Once there was a terrific explosion, they had to be dug out. It was debris from the house next door. Whole streets were destroyed in a single night.

One afternoon, she was walking home with a friend, and there was an air raid. It was broad daylight, and there were no warning sirens. They'd been told that if they were in the open, to hold on to a tree when the planes came. A man across the road called them over, but they said no and held on to the tree. A bomb then fell, and they saw the man fly up into the air. It was awful.

Edna remembers being out after when the department store Edwin Jones was hit. They hadn't picked up the bodies yet, and she saw them all - there were so many. Edna always kept this a secret because she had promised her mum that she would walk around the town and not through it.

One of her most vivid memories was walking to school with her little sisters and carefully stepping over the power lines all over the road after the bombing. Some were still live, and they saw the body of a beautiful Alsatian dog that had been electrocuted. She remembers her sister Barbara, an animal lover, sobbing uncontrollably.

As the blitz worsened, Edna was sent to the countryside. She lied about her age and joined the Land Army. It was hard work. She'd get up at 3:30 a.m. to milk the cows and often worked until midnight to bring in the harvest. In this photo, she is seen standing in front of the same type of tractor she would drive across the fields back then.

German POWs were working on the farm. Edna remembers one called Gerhard. After the war, his parents came over from Germany to thank the farmer for looking after their son so well.

At 95, Edna still lives independently. She does all her cooking, cleaning and gardening and enjoys baking cakes. Her knee plays up, so Edna no longer goes to the shops. Her daughter Sally does the shopping and comes in every day to check that she's okay.

In her 70s, Edna had a triple heart bypass and fully recovered. A neighbour said that it was God's will. Edna said, no, it was the doctor's will.

A few years ago, Edna visited a museum that had reconstructed an air raid shelter. As she stepped inside, all the feelings came flooding back. She had a panic attack and just had to get out of there. Despite occurring over 80 years ago, Edna's memories of The Blitz don't go away.

Angela

Angela Hutor 1913-2023

Angela was born in Cannes in 1913.

When she was just four months old, her mother died of pneumonia. Antibiotics hadn't been invented back then, so it was commonplace for people to die of infection at a young age.

Her dad, who was Italian and worked as a waiter in France, got a foster mother to look after Angela while he went to work.

One of Angela's earliest memories is of WWI. She remembers queuing for potatoes and seeing all the wounded soldiers on stretchers lined up, waiting to be taken for rehabilitation.

Her dad got a job as the head waiter at the Hyde Park Hotel, so he and Angela moved from France to London. Angela was sent to live in a convent school in Chelsea. Nuns ran it and were very strict. She would see her dad every weekend and dread Sunday nights because she would have to return to school.

It took her only a short time to pick up English. Angela has a knack for languages. She can speak French, Italian and German.

Angela has done a variety of different jobs. She's been a hotel receptionist, nanny, seamstress, cashier, florist, shorthand typist and housekeeper.

During The Great Depression, Angela remembers seeing the Jarrow Marchers, who walked from Jarrow to London in 1936 to protest unemployment and poverty. They looked exhausted and walked in silence but seemed so dignified.

During WW2, she worked in a gas meter factory converted to make bomb parts. Being Italian, she was an 'enemy alien' and had to report to the police station every week. She said that despite this, everyone treated her with courtesy.

She remembers the Doodlebug raids (German rockets). They were only a problem once they fell silent, meaning their engines had cut out and were coming down. Once, one whizzed past her when she came home from work in Park Lane.

After the war, she met her husband, Paul. They married at the Chelsea Registry Office and bought their first house in 1950. The house was cheap because it had two sitting tenants, so the couple lived in just two rooms. Times were hard, but Paul was a brilliant handyman, so they saved a fortune on repairs.

Angela had a miscarriage in 1951. The following year, she had their daughter Pauline.

She then passed her exams to become a telephonist at the Continental Exchange in the City. This was shift work, which was ideal because it enabled her to juggle her job and being a Mum.

When Paul was 82, he had a stroke. Angela's knack for languages allowed her to learn the Russian alphabet to communicate with Paul's sister, who lived in Russia.

Paul passed away in the late 90s, and Angela lived independently until 2019 when she moved into a care home.

When she turned 100, she got her card from the Queen. She liked it but joked that she would rather have got a box of chocolates.

As a child, Angela lived through the Spanish Flu pandemic. In 2020, at the age of 107, she contracted the most recent worldwide pandemic, Covid. She was extremely unwell but pulled through and is one of Britain's oldest survivors of the disease.

Angela enjoyed having her photo taken. She was incredibly patient as I fiddled with my camera, trying to get a shot.

Angela's daughter Pauline, who was a massive help with this interview, told me that Angela has always been tolerant and open-minded.

She never judges and has always been a great listener.

She's not one who talks about 'The good old days. She calls them 'the not-so-good old days' and wishes there were things like washing machines, disposable nappies and supermarkets back when she was young. Pauline added that Angela has always loved learning new things and is thankful for everything she has seen and done.

It could be the above attitude that accounts for her longevity. Or perhaps it's her genes. Her dad lived to 106. He retired to Italy and was the oldest man in the country for a while.

Whatever the reason, it was an honour to photograph such an amazing woman.

dorothea

I was in Soho when I spotted a woman waiting on a street corner for a taxi. I thought that she had just come out of a salon because her hair looked so smart. When I told her this, she said, "Darling, it's a wig."

I said that she looked fantastic anyway and asked if I could take a shot. She looked delighted and immediately posed like a pro. I told her that she must've done this before, and she replied, "Of course I have; look me up - my name is Dorothea Phillips, and I'm an actor."

When I got home, I did look her up - Dorothea Melisande Elizabeth Gwenllian Phillips was born 93 years in Glamorgan, Wales. (like most actors of her generation, she had no trace of a Welsh accent at all).

Dorothea has appeared in countless films, theatre productions, and TV shows over the last 70-years, working with the likes of Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, and Peter O' Toole. Her most recent significant role was in 2000 in the movie '102 Dalmations' where she played 'Mrs. Mirthless' alongside Glenn Close and Gerard Depardieu.

I only had time to take one shot of Dorothea as her taxi came almost immediately. As she got in the cab, she turned to me, gave me a genuinely warm smile, and said, "Thank you so much for taking my photograph; you've made my day."

Most people I photograph just about tolerate me taking the shot. So it was great to meet someone who genuinely loved the experience.

Alfreda

Alfreda was born in Austria in 1932 - not long before it became a part of Nazi Germany. She said it was a scary time, but much less so for her than for her Jewish neighbours. Her father was a soldier in WW2 and was killed in action - she didn’t say what side he was on.

After the war, Alfreda married a Royal Navy Officer who later became a policeman. The couple ended up living in Portsmouth. Her husband died several years ago, and she proudly told me she still has his uniform and police notebook.

Alfreda's lifelong passion is Archeology. She spent many years in Luxor, Egypt, studying the Pharaohs. She speaks fluent Arabic, has worked as a belly dancer on cruise ships, and knew the screen legend Omar Sharif. She said he was a charming man but had a real sadness about him because he couldn’t find true love.

The thing that Alfreda wanted to talk about most was the ancient Egyptians. She told me they invented beer, chess, and make-up and that Cleopatra was not remotely attractive. She told me lots of other stuff, but to be honest, I couldn’t take it all in - I wasn’t expecting to get an ancient history lesson from an 87-year-old in a South London pub.

I asked her about the magazine that she was reading. She said, ‘I’m just reading this shit to pass the time,’ and then thanked me for listening to her stories, ‘It’s just so good to have someone to talk to,’ she said.

It was sobering meeting someone who has lived such an eventful life, sitting all alone reading a trashy magazine in a pub with nobody to share her life of learning. She seemed content enough though. As we parted, she thanked me again and said, ‘I’ve had a good life - I haven’t done anybody any harm.’

annie

I met Annie while she was making her way through the crowds at Borough Market.

She was having trouble with her trolley as the wheels were getting stuck in the potholes. I gave her a hand, and she kindly let me take some shots. As I walked her back to her nearby flat, she explained that she had just popped out to get a bottle of whiskey. Her favourite was Johnny Walker, but they don't sell the big bottles anymore in the local mini-mart, so she got some Famous Grouse instead.

Annie was born in the area and has always lived there. Before she got married, she was a machinist in a sportswear factory, but the production was switched to uniforms during the war. Annie has been married twice. Her first husband of 18 years ran off with the barmaid from the Anchor pub, which was a stone's throw from where we were chatting. Ted, her second husband, ran a haulage company, and he and Annie would travel to Spain a lot, which she loved. Ted died last year of dementia at the age of 90. Annie said it was sad because he didn’t recognise her towards the end.

Annie had three kids. The first died at just seven while playing on one of the post-war building sites. He fell through a glass roof. It was ironic because he was told not to play on the bomb sites, so he thought it would be safer to play on a building site instead. Her other son died aged 24. Annie donated one of her kidneys to try and save him, but sadly, he still passed away. Annie’s third child was a daughter. She married an Italian and lives in the South of Italy right next to Mount Etna. She sends Annie videos of the smoking volcano from time to time.

Annie was immaculate in her leather jacket and scarf. She does her own hair and nails, but someone comes in to do her feet. In her youth, she dreamed of being a dancer. She always loved to dance and fancied herself as a bit of a Ginger Rogers. Annie was a very sharp woman, and I enjoyed chatting with her.

Incredibly, Annie will be 93 in June. She was born on the cusp of Gemini and Cancer, so she reads both horoscopes and chooses to believe in the most optimistic one. I’m guessing that it’s precisely that sort of attitude that accounts for her longevity and inherent glamour.

Cathy

Cathy had stopped for a rest on her way home from the shops.

I was out with my dog when I saw this woman sitting outside ‘Lick’, a shop selling designer paint on Northcote Road in South London.

Many well-to-do young couples move into the houses around Northcote Road when they want to start a family. This has made it a desirable place to live, and it has since been named ‘Nappy Valley.' The only older people you see in the area are their parents visiting to spend a day with their grandkids.

I assumed this smartly dressed woman was waiting outside the shop while her daughter and son-in-law chose a paint colour for their kids' nursery.

As usual, I was completely wrong. Catherine has lived in the area for over 50 years. She’d been food shopping and was on the way home, but she had stopped to rest outside a shop. She always walks because lifting her shopping trolley onto the bus requires too much effort.

Catherine has a beautiful Scottish accent. She is originally from Lannark and, after leaving school, worked as the head waitress at the newly opened Butlins holiday camp in Ayr.

She quickly made friends and, once the season finished, went to stay with some of them in Manchester.’ She only did this for a while because she had always dreamed of living in London.

Her mother didn’t want her to go, but she was only 17 and wanted the adventure.

She arrived in London nearly 80 years ago and worked as a waitress in hotels and restaurants. She worked in all sorts of places and told me that back then, you could leave a job one day and start another the next.

“I suited myself. I wanted to get around and meet new people. I had a good time and made lots of friends.”

She worked in a hotel when she met Vincent, a Polish man who was “a very nice chap” and the head waiter.

She and Vincent were good dancers. Because they worked centrally, they would go dancing in the West End, where there were plenty of dancehalls.

They married, had two kids and moved into a house on Bramerton Street in Chelsea.

One day, Vincent was cleaning the windows when a sash cord that held a window in place snapped, making the window abruptly slam shut. This caused Vincent to fall from the ladder to his death. He was only 47.

Cathy never remarried. “You do feel odd—you’re not sure what the kids would think. But that wasn’t what kept me back—I just never had the inkling.”

The rents went up in Chelsea, so Cathy moved South of the river to where she lives now. (Terraced houses in Bramerton Street now sell for up to £8m).

She said that, back in the day, Northcote Road, which is close to where she lives now, used to have a wonderful fruit and vegetable market. It was known to sell particularly good potatoes, and thousands of people would come from all over to get sacks full of them. It was a lovely atmosphere. She misses the noise of the market and the fact that everyone knew each other back then.

She said that nobody really speaks to one another anymore. She comes out her front door and thinks, “Unbelievable - all the years I’ve lived here, I don’t know anyone.”

She says it’s because people come and go so fast. They only seem to live in a house for a year or so, and then they are gone.

She isn’t close with one of her kids, and the other lives in Canada, where her two older sisters also live. She has been to visit them, but it’s too much now at her age, and she knows she’ll never see them again. “It’s sad, but you just have to go on.”

She often thinks about all her friends, “I often wonder, Where are they all, and how come I never hear from them? Then I remember my age, and I realise why.”

Until retirement, Cathy worked behind the counter in shops and grocers and used to do the ‘tallying up in her head.’ Perhaps this explains why the 97-year-old was so incredibly sharp when we chatted.

Although her legs are not too good nowadays, she doesn’t use a stick and doesn’t need reading glasses or a hearing aid.

She says she has a good life and has no complaints. She is happy living where she does; it feels safe, and she wouldn’t want to live elsewhere.

As we parted, she said, “I’m a bit tired now, but I still go on.”

Doreen

I spotted Doreen on London’s King's Road and she kindly let me take a shot.

I hate shooting people in full sun as it’s not the most flattering light. Luckily, this wasn’t a problem with Doreen because she looked so good.

She spoke with an American accent and told me that although she was born in Canada, she spent most of her youth in the USA.

She worked as an air hostess for TWA before becoming an "Ambassador to Hollywood" for the airline. This title was given to flight attendants who worked on glamorous, celebrity-filled routes. Seeing her now, it’s easy to see why she was given the role.

She then worked for years at the American Embassy, which was based in Barclay Square at the time.

Doreen married an Englishman and settled in Kensington. London became her home, and she still lives there today.

She and her husband divorced after about ten years of marriage. Doreen said it wasn’t anyone’s fault; the marriage just didn’t work out.

Doreen is 99 years old, and despite the weather being incredibly changeable that day, she was out for a walk and a look around the shops.

I asked her what her secret was, and she said she had absolutely no idea.

RUTH

Ruth, 82, is the daughter of German Jewish parents who came to London in the late 1930s to escape the rise of fascism. For many years, she worked as a teacher in Kenya, where she married and had two children. Since retiring, she has lived in northwest London.

I took this shot of her at a right-wing anti-immigration march, where Ruth had come as a counter-protester. For safety reasons, the police had kept the anti-fascist counter-protestors apart from the main march, yet somehow Ruth managed to slip through the police lines to find herself among the far-right group. When they shouted, “These streets belong to the British,” she shouted back, “These streets belong to everyone.” She was a lot braver than I was. I didn’t do anything apart from take photos.

Bridget “dilly” Conroy

Like many Irish people, Bridget wasn't known by her birth name. Everybody called her Dilly, short for her middle name, Delia.

She was born on a farm in Tubber, County Clare. Dilly was the eldest of 11.

Times were hard back then, but the farm provided everything the family needed. Early every morning, Dilly would bake soda bread at the hearth, and, being the eldest, she helped raise her younger brothers and sisters. It was a loving family, and Dilly had a good childhood.

She left school when she was about 13 and worked for the family of the local GP, helping to raise their children.

She moved to London in 1943 during the war and worked as a cook. In 1947, she secured a job cooking for Ernest Bevin, the then-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. The address, the sumptuous No. 1 Carlton Gardens, must've been quite a culture shock for young Dilly, who was from a small farmhouse back in County Clare inhabited by a family of 13.

But she must’ve taken it in her stride because a few years later, she became an assistant cook at Buckingham Palace. She was the first woman to hold this role, as traditionally, the cooks at the palace were always men.

In 1953, Dilly went to Clarence House, where she worked for the Queen Mother. This job took her all over the world. She met countless dignitaries, knew all the members of the Royal Family and in 1979, was awarded the Royal Victorian Medal for her service by the Queen. She retired in 1985 after working for the Royals for over 30 years.

When I first met Dilly, she was 103 years old and living in a care home run by nuns, where she was again known by her birth name, Bridget. By then, she had Dementia.

We met in the lunchroom, where she had soup, roast lamb with all the trimmings, followed by trifle, with orange squash to drink. The staff cut up the food, but she ate the whole meal unaided and enjoyed it.

Her only concern was that I wasn't eating and kept asking if I wanted to eat something.

After lunch, Bridget went off to a quiet spot at the end of a hall and happily sat there for hours, clutching her immaculate leather handbag - just like her old boss.

She was at the end of a corridor when I returned a few days later with the photo I had taken during lunch.

She was pleased with the photo, but as she held it in her hands, she didn't see herself in it. She said, "Oh, what a beautiful young woman and such a lovely white hat." Then, gesturing towards the end of the empty corridor, she asked, "Was it you who built the stage? Did you put up those beautiful curtains?" There was nothing there. "It's such a marvellous job you've done. Are you married yet? Have you got yourself a wife?" She looked directly at me, but I felt that she was speaking to someone from long ago. I replied that I was married. Bridget smiled warmly and appeared satisfied. "I'm so pleased. Do you have babies? You have to have babies?".

I told her I had a son and a daughter. She said, "I bet when you get home from the fields, they pull at your legs asking for sweets?" She repeated, "I bet they ask you for sweets?"

I told her that my kids (now in their twenties) loved sweets. Bridget then smiled to herself and went back to looking at the photo. "That's such a lovely hat that she's wearing".

She may have had Dementia, but she always seemed perfectly happy whenever I saw her. This is undoubtedly due to the excellent care she gets at the home. Her clothes were immaculate, and her hair always brushed. She was never in danger because there's no way she could physically leave the place. However, Bridget's mind took her way beyond the walls of the building.

Interestingly, whenever I met her, she never once mentioned her decades in London, the Royal Family or her incredible career. It was always her beloved Ireland and village life that filled her mind.

On another visit, a carer wheeled her into the TV room. She didn't like this and wheeled herself back to her spot at the end of the corridor. To Bridget, her thoughts of past times back in the village were far more interesting than daytime TV.

Bridget passed away recently. She was 105 years old. RIP Bridget 'Dilly' Conroy. 1920-2025.